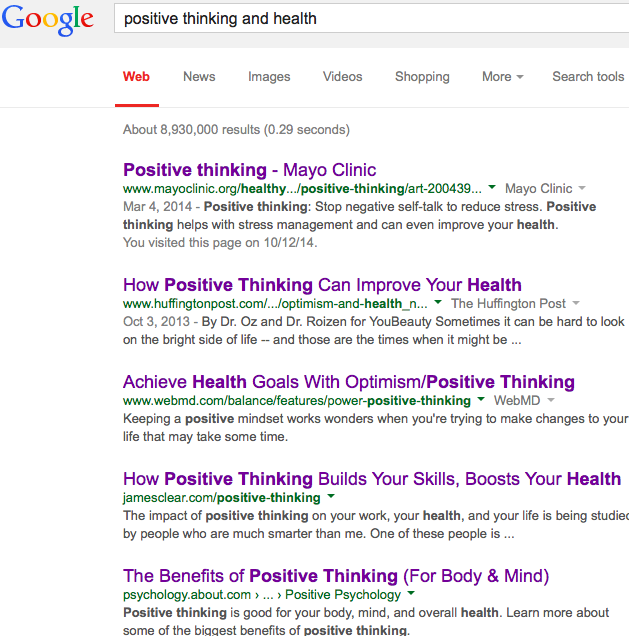

Ever hear “you have to stay positive when you’re sick,” implying that positive thinking can make you better? Me too, a lot in fact. As a kid in the hospital, I heard that one plenty, so I wanted to investigate. Can positive thinking improve one’s physical health? Does the condition matter? Does stress come into the equation? First, I looked into studies that claimed positive thinking as a health benefit.

Ever hear “you have to stay positive when you’re sick,” implying that positive thinking can make you better? Me too, a lot in fact. As a kid in the hospital, I heard that one plenty, so I wanted to investigate. Can positive thinking improve one’s physical health? Does the condition matter? Does stress come into the equation? First, I looked into studies that claimed positive thinking as a health benefit.

Study #1: Over five years, Steven Greer and his colleagues followed the physical and psychological conditions of 578 women who had enrolled in the study with early-stage breast cancer. Early on they classified women in “helplessness/hopelessness” or “fighting spirit” categories based on their answers to surveys. At the end, women with high “helpless/hopeless” scores were more likely to relapse or die within five years than women with a “fighting spirit.” Study #2: Next, men undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery were interviewed before the surgery, a few days after surgery, and then again months later. Researchers used the LOT (Life Orientation Test) to convert people’s statements about their expectations for their future health to scores to evaluate optimism. Men classified as “optimists” had fewer negative physiological changes in their electrocardiograms and fewer releases of enzymes into the bloodstream that could cause infections. Basically, the data showed that pessimists were more likely to suffer heart attacks during surgery. Pessimism also seemed to be related to slower recovery. Study #3: In 2001 researchers found that amongst war veterans, veterans determined by personality inventories to be optimists were less likely to develop heart disease than the veterans classified as pessimists. The researchers determined this result was independent (meaning not affected by) smoking habits.

In fact, further studies have found no significant data demonstrating that positive thinking improves health. The meta-analysis called “Positive Psychology in Cancer Care: Bad Science…,” reviewed 12 studies that examined the effect of “fighting spirit” on cancer progression and survival. The ten larger studies found negative results, and only the two smaller, flawed, and confounded studies found results that supported the claim that positivity improves health. They cite another meta-analysis that says positive thinking has no significant improvement effect on cardiovascular diseases or cancer. The American Cancer Society even discounts the health benefits of positive thinking.

How can we explain the results of the three studies and many others that say there is a link? First: most studies have a potential reverse causality—instead of positive thinking improving a person’s health, a person who becomes healthier could improve their attitude. Potential confounding variables (like lower SES and education) and small sample size influenced other results. In “Thinking differently about thinking positive,” Sue Wilkinson and Celia Kitzinger pointed out that especially in the world of breast cancer, patients feel a lot of pressure to think positively, which could coerce subjects to report more positivity than they actually feel. The questionnaires and surveys themselves can also be ambiguous, and the coding of patients’ answers is inconsistent. In one study the phrase “I try to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive” was coded as positive thinking while “It’s best to be positive at all times. I try not to let myself get depressed, sad, or angry when things go wrong” was coded as the less positive “Type C personality” that allegedly increased risk of cancer. Inconsistent modes of measurement of positivity mean that the results are not reliable. Some also thought that stress influenced the results of conditions like heart disease and Alzheimer’s that are connected to stress. But data shows positive people are not necessarily less stressed than negative people, nor do coping methods of stress (good vs. bad) make a significant difference in physical health.

So why do some still believe that positive thinking cures? Here’s my thought: when I was in the hospital as a kid, I liked to think that if I behaved and stayed positive I would get better. When facing terrifying illnesses, people want to do something, doctors want to as well, and the idea that positive thinking could help is comforting and within someone’s control. There might be perceptual bias like that of the doctors mentioned in class: Believers of positivity may think if they get healthier, it’s because they were positive, and if they don’t, it’s because the disease was really tough. All of that is understandable, I’ve been there, and no one likes to feel helpless. But the ACS sums it up well: Positive thinking therapy may improve quality of life, but it doesn’t prevent or cure disease. Take home message is wishing doesn’t make it so.