By: Jacob Ryder

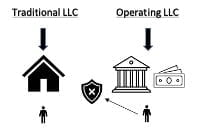

Investing in rental real estate provides two main financial benefits: monthly cash flow from rental income and appreciation in home values. While these are substantial benefits for building wealth, there are also significant risks. The risk of extended vacancies, tenants who damage your property, and – the largest risk of all – the threat of personal exposure, can be daunting. The risk of being forced to use personal assets to satisfy debts incurred through rental activity has driven many investors to form LLCs for real estate investing. These types of investors (let’s call them ‘traditional LLC’ investors) purchase the rental property through an LLC to protect what they have worked so hard for – their personal assets. Personal ownership of rental property gives a creditor a direct line to use your personal assets to satisfy debts, including legal judgments.

Investing in rental real estate provides two main financial benefits: monthly cash flow from rental income and appreciation in home values. While these are substantial benefits for building wealth, there are also significant risks. The risk of extended vacancies, tenants who damage your property, and – the largest risk of all – the threat of personal exposure, can be daunting. The risk of being forced to use personal assets to satisfy debts incurred through rental activity has driven many investors to form LLCs for real estate investing. These types of investors (let’s call them ‘traditional LLC’ investors) purchase the rental property through an LLC to protect what they have worked so hard for – their personal assets. Personal ownership of rental property gives a creditor a direct line to use your personal assets to satisfy debts, including legal judgments.

When done properly, an LLC forms a ‘brick wall’ to cut off the direct line between creditors and your personal assets. While a traditional LLC investor might have an ‘LLC wall’ to protect personal assets from creditors, what about protecting the real estate asset that generates their financial returns? This is where the ‘traditional’ LLC investor’s formation falls short.

When done properly, an LLC forms a ‘brick wall’ to cut off the direct line between creditors and your personal assets. While a traditional LLC investor might have an ‘LLC wall’ to protect personal assets from creditors, what about protecting the real estate asset that generates their financial returns? This is where the ‘traditional’ LLC investor’s formation falls short.

Will Property Insurance Cover it?

The traditional LLC investor’s rental property is not without any protection. If the investor went through the process of forming an LLC to avoid risk, there is a good chance the investor has also purchased insurance. While general property insurance will protect the structure from damage caused by wind, fire, hail, or lightning, this discussion centers on liability insurance and its shortfalls.

The traditional LLC investor’s rental property is not without any protection. If the investor went through the process of forming an LLC to avoid risk, there is a good chance the investor has also purchased insurance. While general property insurance will protect the structure from damage caused by wind, fire, hail, or lightning, this discussion centers on liability insurance and its shortfalls.

While a good thing to have, liability insurance protects the real estate investment from only a few, although arguably the most common, kinds of creditor actions in real estate investing. Generally, insurance protects against negligence – claims that the entity did not exercise ‘reasonable care’ in actions concerning the real estate asset and that the creditor was injured as a result. This ‘partial protection’ will fully protect the real estate asset in circumstances where there is coverage, but it will provide no protection where there is none. Claims that may not be covered by liability insurance include breach of contract, fraud, and other claims alleging intentional conduct. Without coverage, a direct line remains between the creditor and the real estate asset. The investor who already formed an LLC and purchased insurance to minimize risk has to ask, “How do I protect myself from this insurance blind spot?”

Two LLC Formation

As the traditional LLC investor, you already formed one LLC to protect your personal assets. Why not form another LLC to protect your real estate asset? Using two LLCs can offer protection for the insurance blind spot. The set-up is simple. The first of the two LLCs, the ‘traditional’ or ‘holding’ LLC, will only own the rental property. The second LLC, the ‘operating’ LLC, will handle everything, including every interaction with a tenant, repairman, or property management company. This LLC should have a bank account with enough money to pay for repairs as they become necessary. Therefore, the investor’s exposure is limited to the amount of money in the ‘operating’ LLC’s bank account. This protects in a similar way to the ‘LLC wall’ explained in the ‘traditional’ formation, but this time, it separates the rental property itself from creditors.

As the traditional LLC investor, you already formed one LLC to protect your personal assets. Why not form another LLC to protect your real estate asset? Using two LLCs can offer protection for the insurance blind spot. The set-up is simple. The first of the two LLCs, the ‘traditional’ or ‘holding’ LLC, will only own the rental property. The second LLC, the ‘operating’ LLC, will handle everything, including every interaction with a tenant, repairman, or property management company. This LLC should have a bank account with enough money to pay for repairs as they become necessary. Therefore, the investor’s exposure is limited to the amount of money in the ‘operating’ LLC’s bank account. This protects in a similar way to the ‘LLC wall’ explained in the ‘traditional’ formation, but this time, it separates the rental property itself from creditors.

Illustration

Suppose Stacy, an investor, owns a multifamily rental property in town. The unit is valued at $100,000, and she used $30,000 of her own money to finance a purchase through an LLC. She has two happy tenants and collects $1,200 a month in rental income. Unfortunately, a tenant misunderstands what was promised in the lease, and the tenant brings a claim for breach of contract. While likely unrealistic, assume a court awards the tenant $75,000 in damages for the LLC’s breach of contract.

In the first scenario, let’s assume Stacy has the ‘traditional’ LLC formation to own her rental property. The lawsuit, in this case, would be against the same entity that owns the rental property. This is terrible news for Stacy. The creditor can attach the judgment against the property and possibly force the LLC to sell it. In this scenario, Stacy will only keep the rental property if she can fund the LLC with $75,000 and satisfy the debt. Otherwise, her best course of action will likely be to sell the rental property.

In the second scenario, let’s assume Stacy created the two LLC formation. In this case, the tenant will sue the entity it interacted with, the ‘operating LLC,’ which, as described above, only owns a bank account. Let’s assume there is $6,000, or five months of rental income, in the operating LLC’s bank account. By using two LLCs, Stacy has put up another ‘LLC wall’ between the creditor and her investment. Stacy’s risk in this scenario, instead of $75,000 worth of the rental unit, is only $6,000. Stacy can rest easy knowing that the creditor cannot force her to sell her rental property to pay off the debt.

In the second scenario, let’s assume Stacy created the two LLC formation. In this case, the tenant will sue the entity it interacted with, the ‘operating LLC,’ which, as described above, only owns a bank account. Let’s assume there is $6,000, or five months of rental income, in the operating LLC’s bank account. By using two LLCs, Stacy has put up another ‘LLC wall’ between the creditor and her investment. Stacy’s risk in this scenario, instead of $75,000 worth of the rental unit, is only $6,000. Stacy can rest easy knowing that the creditor cannot force her to sell her rental property to pay off the debt.

Benefits and Costs

The two LLC formation not only protects personal assets, but it can also protect the rental property – something the investor worked equally hard for – when insurance does not. However, this is not a perfect solution. LLC ownership risks still exist, including the risks that a court will disregard the entity if the investor mixes business and personal funds and the risk that the individual will be directly liable for any acts they personally commit. There are also additional costs to form and maintain another LLC.

The ‘traditional LLC’ may protect your personal assets, but it leaves only the partial umbrella of insurance to protect your investment. Forming two LLCs can protect what insurance does not. Before choosing a form of entity, an investor should always weigh its costs and benefits. No solution fits every investor, and as always, an investor should always consult with an experienced attorney before making any legal decision.

This post has been reproduced with the author’s permission. It was originally authored on February 11, 2021, and can be found here.

Jacob Ryder, at the time of this post, is a 2021 graduate of Penn State Dickinson School of Law. Prior to moving to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to attend Dickinson Law, he was a resident of Olney, Maryland. He attended Towson University in Baltimore, Maryland where he earned his bachelors degree and played four years of Division 1AA football. Jacob was a comment editor for Dickinson Law Review and a research assistant for the professors who work in the Law Library. Following graduation, he will be pursuing his interest in business law as an associate at Morris, Nichols, Arsht & Tunnell in Wilmington, Delaware.

Jacob Ryder, at the time of this post, is a 2021 graduate of Penn State Dickinson School of Law. Prior to moving to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to attend Dickinson Law, he was a resident of Olney, Maryland. He attended Towson University in Baltimore, Maryland where he earned his bachelors degree and played four years of Division 1AA football. Jacob was a comment editor for Dickinson Law Review and a research assistant for the professors who work in the Law Library. Following graduation, he will be pursuing his interest in business law as an associate at Morris, Nichols, Arsht & Tunnell in Wilmington, Delaware.

Sources

Smith v. Wells, 212 A.3d 554, 557 (Pa. Super. 2019).

Ward and Smith, P.A. (October 14, 2016) https://bit.ly/3p8aPiU.

Hyojung Lee, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (August 18, 2017) https://bit.ly/2MRiy80.

Allstate, Homeowners Insurance vs. Landlord Insurance for a Rental Property (Updated January 2019) https://al.st/2Z2et3q.

Pennsylvania Department of State, Business Fees & Payments (last visited February 10, 2021) https://bit.ly/3p6ZyPV.

Photo Sources