By Colette Slagle and Jacqui Reid-Walsh 1817 Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

1817 Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

This week we began engaging with the Metamorphosis texts differently—not as a set of narrative episodes directed by the panels, but as a literacy abecedary. Instead of following the directives in the text to turn-up and turn-down the flaps, attending to the alphabet requires opening and laying out all of the flaps at once. The alphabet is displayed horizontally across the length of the open artifact. Interestingly, if you follow the directions in the text and turn the flaps up and down in the intended manner, the order of the alphabet is disrupted. For example, in the first panel the letters revealed when opening the flaps read “A B C C D D” across the top, followed by “U V W X Y” across the bottom.

The letters are printed in the upper and lower border of the central images, but bear no obvious relation to the images or the accompanying verse. Although an alphabet is textual, in this case it is not printed by the metal type, but is part of the woodblock illustrations. We ascertained this by comparing Sands and Poupard’s editions to G.S. Peters’ editions. The images and alphabet remain the same across the Sands and Poupard editions, but when Peters changes the images in his editions, the alphabet also changes.

1831 (1960 facsimile) Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

We also noticed that the alphabet border resembles the style of a sampler. For example, the letters are all capitalized and are on a faintly lined background. The letter style is also ornate and appears “stitched” rather than printed in the standardized letterpress style.

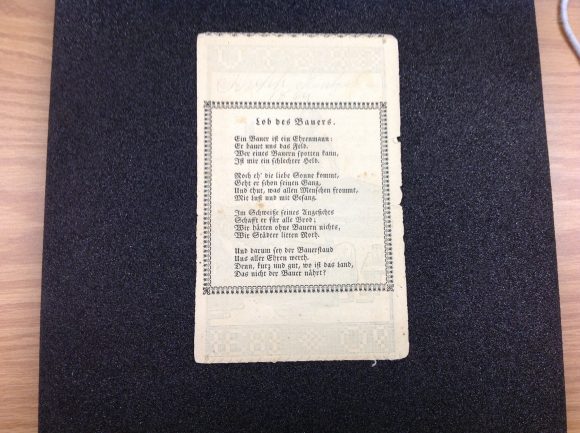

1853 Sampler by Anna Timmis. M974.119.2. Photo Courtesy of McCord Museum.

1853 Sampler by Anna Timmis. M974.119.2. Photo Courtesy of McCord Museum.

Some of the letters appear twice—one in a more basic style, and one in a more ornate style. Curiously, not all of the letters appear this way, only C, D, I, and T have duplicates. This partly seems to follow the sampler style which would sometimes duplicate the whole alphabet in capital letters. We are still puzzled as to why only certain letters are duplicated in the Metamorphosis. Perhaps it is only due to the allotment of space and the chosen letters are arbitrary.

Moreover, while there is a double “I”—one simple and one ornate—there is no “J” present. The history of the English alphabet is complex and the development is not perfectly linear. According to E. Jennifer Monaghan in Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (2005), the authors of spellers “differed about the treatment of the consonantal i and u (which eventually became the j and v of the modern alphabet)” (216). Interestingly, the Metamorphosis has both the letters “U” and “V” but no “J”. While no “J” is listed in the alphabet, it is used in the text: “There nothing could their joys controul” (emphasis added)—even more interesting is that it is used in the same panel that the double I (and absent J) appears.

1817 Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

1817 Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

The inclusion of a secret alphabet hidden inside the flaps may have been intended for utilitarian purposes, indeed, an 1814 edition of the text printed by Robert Porter makes this clear through the subtitle: “also, an alphabet of large and small letters to aid females in marking linen.” At the same time, however, there could be a more playful option. One possible educational game that could emerge from the object would be matching some of the letters to the images in the text when all of the flaps are open. For example, “A for Adam or Apple,” “E for Eve, Eden, or Eagle,” “L for Lion,” “G for Griffin,” “S for Serpent,” etc.

We then began to question if there were any possible image connections with the missing letter “J.” We did not find many, but one possibility is that the empty scales featured in the third panel with the wealthy merchant could be read as an allusion to the “scales of justice,” particularly as the verses in the fourth panel condemn his greed.

1817 Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.

1817 Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Photo courtesy of Penn State Special Collections.