By Colette Slagle and Jacqui Reid-Walsh

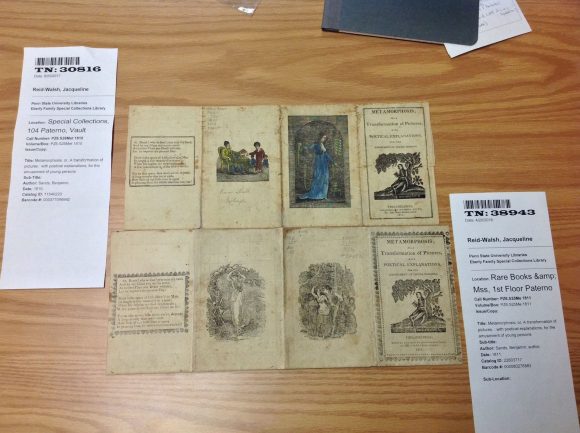

At the beginning of this school year, Jacqui and I wrote a blog in which we compared the 1810 Metamorphosis book printed by Solomon Wiatt and the 1811 Metamorphosis book printed by Jonathan Pounder (held at the Bodleian Library). Penn State Special Collections recently purchased an 1811 Metamorphosis book printed by Joseph Rakestraw. Today, we decided to revisit the 1810 Metamorphosis book held at Penn State, and compare it to the newly purchased 1811 Metamorphosis book, due to the close proximity of their publishing dates and locations.

The 1810 version was published by Solomon Wiatt at No. 104, North Second Street, Philadelphia, PA. The 1811 version was printed and sold by Joseph Rakestraw at No. 248, North Third Street, Philadelphia, PA. These two addresses appear to be only one street apart from one another. The similarities between the two versions are striking; however; they are not without differences.

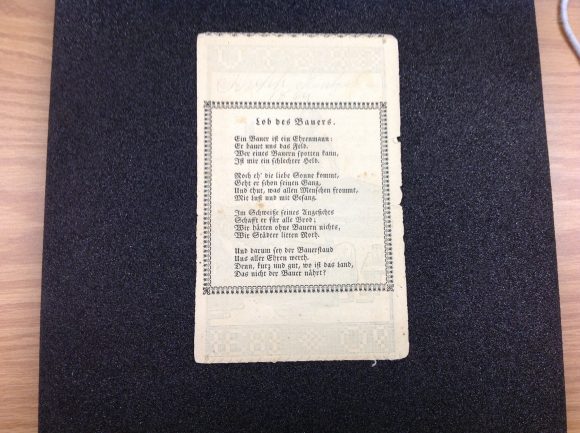

The images in the main text of both versions are identical, though the images on the verso differ. In Wiatt’s 1810 version, there is an image of a man seated in a chair and handing a little boy a book, and an image of a woman in chains in prison. In Rakestraw’s 1811 version, there is an image of a woman beneath a tree with a reclining African American man beside her, and an image of a couple fleeing. The title pages also both feature the same image of a man sitting underneath a tree. According to Welch, Wiatt’s 1810 version is the first one to feature this image (392).

Verso of Wiatt’s 1810 version (top) and verso of Rakestraw’s 1811 version (bottom) (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Verso of Wiatt’s 1810 version (top) and verso of Rakestraw’s 1811 version (bottom) (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Interestingly, Rakestraw’s 1811 version and Pounder’s 1811 version are completely identical in the images they use, including the extra images on the verso.

Verso of Jonathan Pounder’s 1811 version. (Bodleian Library, Oxford University Vet. K6 f.92)

Verso of Jonathan Pounder’s 1811 version. (Bodleian Library, Oxford University Vet. K6 f.92)

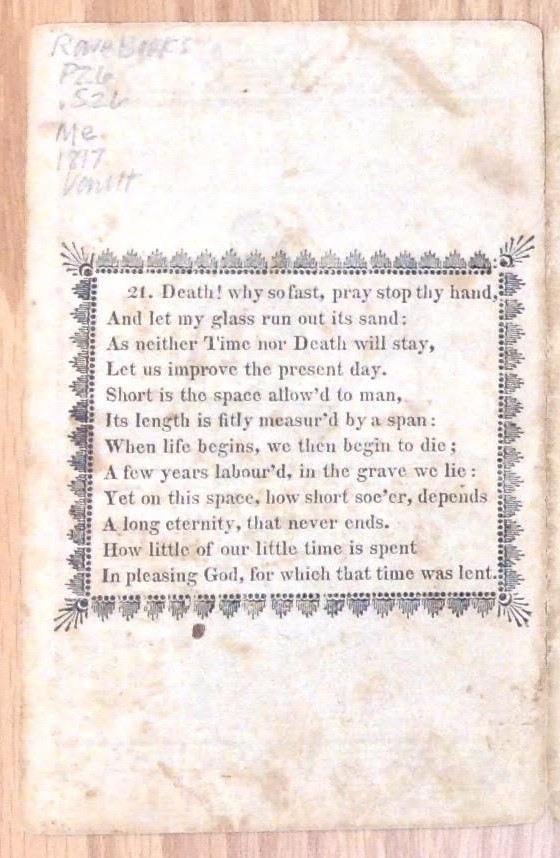

The text in Wiatt’s 1810 and Rakestraw’s 1811 is also identical, with only a couple of minor differences, likely due to typographical errors (i.e. the occasional missing comma, and the misspelling of “Saviour” as “Savour” in Rakestraw’s 1811 version).

Misspelling of “Saviour” as “Savour” in Rakestraw’s 1811 version. (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Misspelling of “Saviour” as “Savour” in Rakestraw’s 1811 version. (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

The biggest differences, however, were not in the images or the text. The most striking difference is the size of the paper. The 1811 version printed by Rakestraw is visibly larger. It measures approximately 14 ¼ inches x 5 ¾ inches, while the 1810 version published by Wiatt is approximately 13 ½ inches x 5 5/8 inches. This means that the difference in length between the two is about ¾ of an inch, and the difference in width is about 1/8 of an inch. While the widths of the two texts are very close in size, the lengths are significantly different.

Wiatt’s 1810 version (top) and Rakestraw’s 1811 version (bottom). (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Wiatt’s 1810 version (top) and Rakestraw’s 1811 version (bottom). (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Another interesting difference between the two are the borders used in each version. In the 1810 version by Wiatt, when the flaps are closed, the borders around the text are straight and rectangular, except for the set of verses numbered 7 on the top flap of the third panel. Here, the border is a wavy line rather than a straight line.

Wiatt’s 1810 version (top) and Rakestraw’s 1811 version (bottom). (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Wiatt’s 1810 version (top) and Rakestraw’s 1811 version (bottom). (Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

When the flaps are open in the 1810 version by Wiatt, they all have wavy borders around the text, matching the 1811 version by Rakestraw. The only difference between these two versions when all of the flaps are open is the dividing lines between the original verses and the added verses. In Rakestraw’s 1811 version, all of the dividing lines are wavy, matching the borders that surround the text. In Wiatt’s 1810 version, however, the dividing line has a different design, with the exception of the top flap on panel one featuring sets of verses numbered 13 and 2, which strangely matches the wavy dividing line of Rakestraw’s 1811 version.

Wiatt’s 1810 version. The wavy dividing line featured on the left matches the wavy dividing lines used in Rakestraw’s 1811 version. Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

Wiatt’s 1810 version. The wavy dividing line featured on the left matches the wavy dividing lines used in Rakestraw’s 1811 version. Special Collections, Penn State Libraries)

We have enjoyed comparing these two texts and going forward we are excited to look at other versions of Metamorphosis books that are presently being catalogued at Penn State. With the help of curator Jose Guerrero, Jacqui was able to locate a few more versions. In addition to the 1811 version, there are 1815 and 1816 versions, both also printed by Joseph Rakestraw. This means that Penn State now holds editions printed by Rakestraw from 1811, 1814, 1815 (a hand-colored version), 1816, and 1817, which we are excited to compare when we return in the fall.