By Jacqueline Reid-Walsh and Colette Slagle

Since coming back from England mid-May, one joy has been going to Rare Books once a week. When visiting home in Montreal over the summer, I went to McGill; now that I am starting back in State College, I am making my first visits to Special Collections at Penn State. While in Oxford I was encouraged to pursue my close comparisons of the Beginning, Progress and End of Man with the Metamorphosis books and with the homemade versions. Not the least important discovery is my learning of a German language tradition from collectors Mr. Alcock and Mr. Temperly, and through email on the project website to (retired curator) Sandra Stelts a German scholar Dr. Schultz who has written articles on the subject. These I can admire only in terms of the visuals but am looking for someone to translate for me for a modest sum.

One way to extend my project thinking is my aim to teach myself quasi or semi-diplomatic transcription since I realized that no two versions of the turn-up books were the same. My questions concern how to recognize which changes are trivial and which are important. To do this, I came to appreciate that apart from carefully photographing the items, I needed a detailed transcription of each text. I first became acquainted with this process when sitting in on Dr. Richard Virr’s classes in descriptive bibliography at McGill where they transcribed ornate title pages of early printed books. I thought, yes, it makes sense with those priceless objects, but what about 17th -19th century “cheap print” and children’s and families’ homemade texts?

In Oxford I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Giles Bergel and learning about his digital project devoted to the variants of the ballad, “The Wandering Jew” at: http://wjc.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/

Apart from the fact he is a computer whiz and a literary scholar, his project is devoted to another “cheap print” text and one component is this kind of transcription. Here my question was—how detailed should this be? Just before leaving England, I copied a couple of Metamorphosis in the Bodleian in a cursory way along with my research assistant Colette Slagle. Over the summer I looked repeatedly at several copies of the Metamamophosis at McGill. First, I practiced normalizing the spelling and ignoring the font style of the verses, but soon realised this reduced the visual dimension and the characteristics and individual spelling of the verses.

What is semi-diplomatic transcription anyway? In “Electronic Textual Editing: Levels of transcription” by M. J. Driscoll on the TEI or text encoding initiative at http://www.tei-c.org/About/Archive_new/ETE/Preview/driscoll.xml, I found clear definitions and examples. Driscoll defines diplomatic transcription in the following way:

“[T]here are transcriptions which may be called strictly diplomatic, in which every feature which may reasonably be reproduced in print is retained. These features include not only spelling and punctuation, but also capitalization, word division and variant letter forms. The layout of the page is also retained, in terms of line-division, large initials, etc. Any abbreviations in the text will not be expanded, and, in the strictest diplomatic transcriptions, apparent slips of the pen will remain uncorrected.”

Recalling sitting in on Dr. Richard Virr’s descriptive bibliography class, I realised this is what the students were doing with the frontispieces of the early printed books they were examining.

Driscoll’s notes go on to state that the opposite process is fully normalized transcriptions, which hardly seem like transcriptions, especially with early materials. I discovered this with my attempts to modernize the spelling and fonts of the over 50 printed Metamorphic books since the verses are in many cases close to one another, so the differences reside not only in occasional verse alternations and additions but also in how they are represented by the printers over a hundred-year period.

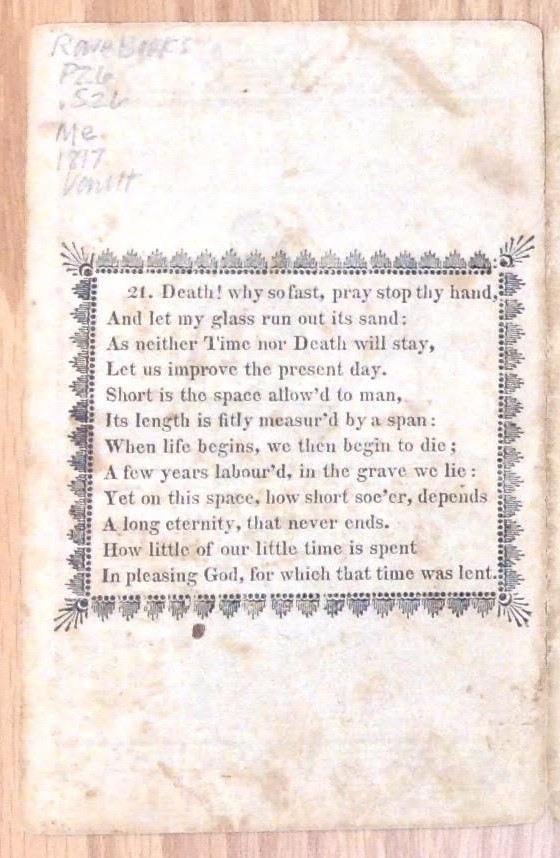

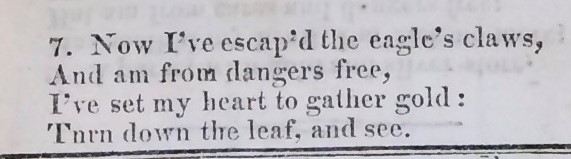

The article says that the in-between method is called semi-diplomatic or semi-normalized—but how much in either direction? I looked over the list of aspects: Forms of letters, punctuation, capitalization, structure and layout, abbreviations, corrections and emendations. I realise that although many of the examples are from scribal culture or early printed books, I would like to make the transcription as “diplomatic” as possible (love the pun). My logic is that the visual aspect in the piece is as important at the verbal, and that the visual encompasses not only the woodcut illustrations but the presentation and the appearance of the verse.

Accordingly, I have decided that I want to reproduce the visual effects of typographical variants, such as the long s that looks like an f, capitalizations, abbreviations, the contractions, the punctuation and spelling, and importantly the structure and layout since the text is verse. Although this may be too detailed, it may help me understand the changes the text underwent over the years. Since the illustrations were often updated, I am interested in whether the temporal “modernizations” occurred on both the verse and the woodcuts together or not. Now that I am back at Penn State looking at the published and homemade versions, I realise that the quasi or semi-diplomatic transcript is the format I need to learn to use.

As shown by the automatic spell check in the transcription, the word processor marks a non-normalized word as an error. As I have come to realise, the contractions capture the informal tone of the speaking voice that would be erased by normalized spelling.

Another avenue of questioning, which we will address in a later blog, concerns the paratextual matter of the sampler-like letters and numbers that are also different in some books. I need to learn more about how they were printed. They surround the woodcut illustrations yet feature capital letters—were they set with regular type or special carved blocks?

1814 version with mending tape. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections) For larger view see image gallery page of website.

1814 version with mending tape. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections) For larger view see image gallery page of website.