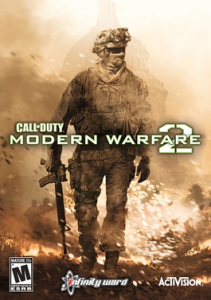

I do not play video games often. When I do, it is often a sporting game such as NBA 2K or Madden NFL with a couple of buddies after a late night. However, back in my adolescent years I would spend my days and nights playing Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 with my fellow immature youngsters.

For those who are not familiar with Call of Duty, it is a video game where you are equipped with a gun in a war simulation and try to shoot as many people as possible. While this video game is rated M for mature, many teenagers, and even children around the age of nine, get their hands on a copy of this game through Amazon or simply by asking their parents to buy it for them.

There seems to be a rising consensus that video games such as Call of Duty enhance violence in teenagers. As somebody who used to play these types of games religiously, I am confused by this hypothesis. I didn’t have any urge for violence after playing Call of Duty, nor do I now. So am I an outlier or do violent video games simply do nothing? Luckily the internet is available to research these things, and this article from The Telegraph seems to give an answer to this question.

Research from Canada’s Brock University tried to answer this question by conducting a study with 1,492 kids in their pre-teen years (Telegraph 2012). These kids were picked from eight different schools (Telegraph 2012). These children (aged 14 to 15) were then asked survey questions every year for four years in an observational study and their answers were then calculated into what could be called an aggressive level (Telegraph 2012).  The questions asked by the researchers included the number of times they pushed or shoved another student or whether they punched or kicked another student due to a feeling of anger (Telegraph 2012). They found that the students’s aggressive scores rose over the years as they played violent video games.

The questions asked by the researchers included the number of times they pushed or shoved another student or whether they punched or kicked another student due to a feeling of anger (Telegraph 2012). They found that the students’s aggressive scores rose over the years as they played violent video games.

But what about confounding variables from this experiments? Well they took this into account. Gender, divorcing of parents, and use of marijuana were all taken into account in this study yet the results remained the same (Telegraph 2012).

However, a conflicting study revealed a different result. This study was conducted by Oxford University and found that kids do not get more violent by playing video games. 200 children aged 10-11 were asked about how often they played video game (Bingham 2015). While this study did find kids who played video games were more aggressive, they found that it was due to number of hours played and not the amount of violence in the game (Bingham 2015).  The leader of this study said previous studies did not compare violent video games with games that involve the same feeling of competition you find in other games (Bingham 2015).

The leader of this study said previous studies did not compare violent video games with games that involve the same feeling of competition you find in other games (Bingham 2015).

So could this be a case of the Texas Sharpshooter problem? Could the wrong similarities have been stressed while ignoring key pieces of data? It is quite possible.

But maybe this study by Oxford was a false negative. We will have to wait and see as more studies on this topic are conducted.

A meta-analysis must be done! If there were many, many more studies done on this topic and the studies were complied, it will be a much stronger evidence than a single study or two. For example, in the “does prayer help cure patients” research we learned about a while ago in class, while one well conducted study was done and found prayer did help, it was disproven because the meta-analysis was so convincing. When more and more studies were done, the study that said praying does help was revealed to be a case of chance. Once there are many studies to base a conclusion on, chance starts to decrease as you get the same result by repeating or compiling different studies with the same objective. If a meta-analysis is done for this video-game conundrum, we will surely get a definitive answer on whether video games truly do cause violence.