My staple breakfast meal at a diner consists of bacon, rye toast, home fries, and two poached eggs with runny yolks. It may sound insanely weird, but my favorite part of breakfast is the moment I dip my rye toast into my runny egg yolks. However, I’ve always heard rumors that egg yolks are actually extremely unhealthy. Although eggs are a great source of iron, vitamins, and nutrients, they contain a large amount of dietary cholesterol. Excessive amounts of cholesterol can negatively affect heart health (Heid). So my question is, are egg yolks actually THAT unhealthy for me?

In 2012, a Canadian study was conducted to research this question. This observational study implemented an ultrasound test to observe the buildup of fat in the arteries of 1,231 adults. Every participant in this study was a regular at a vascular prevention clinic due to pre-existing signs of heart disease. The alternative hypothesis tested was the effect that a large consumptions of egg yolks had on heart disease. Although this is an observational study, reverse causation can be ruled out due to time, since heart disease cannot be the cause of food consumption that already occurred. As always, chance is an option in this experiment, and many third variables could affect the correlation, such as junk food consumption, lack of exercise, and hereditary risk of heart disease.

diagram of carotid artery found here!

Besides observing each participant’s carotid arteries via ultrasound, the researchers also asked every person to do the following:

- Explain his/her personal history of smoking

- List how many egg yolks he/she consumes in a week

- Recall how long he/she had been eating this weekly amount of egg yolks

With this data and information, researchers concluded that the more a person smoked and the more egg yolks a person ate both increased a person’s risk for heart disease. However, there are quite a few faulty limitations that hold this study back. For starters, this is a single, small study, and is extremely exclusive considering the participants are already at risk for heart disease, and are all Canadian. Second, just as our intuition is lousy, so is our memory. Many participants could simply be generalizing their egg yolk consumption and cigarette smoking throughout the years. This study definitely highlights a correlation between smoking, egg yolk consumption, and increased risk for heart disease. However, it is not large enough or conducted strongly enough to prove any causation. Personally, I think the only way to conclude a strong correlation would be to conduct a meta-analysis of similar studies.

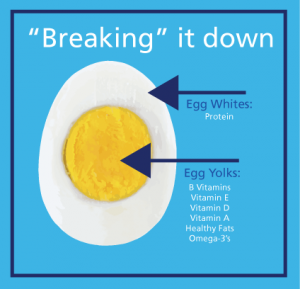

On the other side of the spectrum, this U.S. News article by Toby Amidor argues in favor of egg yolks. An important point brought up in Amidor’s article is the fact that other foods in our daily diets, such as meats and dairy, contain just as much fat as the average egg yolk. So, if we are told to avoid egg yolks for this reason, then shouldn’t we be avoiding chicken, beef, pork, yogurt, cheese, and milk as well? At that point, we would all basically be vegans! Amidor’s article also highlights the American Heart Association’s approval of the entire egg, not just the whites, and according to Blue Cross Blue Shield of Mississippi, other breakfast foods that complement morning eggs are the actual sources of bad cholesterol.

What I’ve taken away from my time researching egg yolks is that the unhealthiness of an egg yolk probably exists, but not enough to cut yolks out of my diet completely, especially if I’m not at risk for heart disease. In reality, if my morning eggs are the fattiest foods I consume during the day, am I really doing that much harm to myself? Surely, people who are pre-disposed for heart disease may want to watch excessive egg yolk consumption, but observing a healthy diet as a whole instead of cheating oneself out of one specific food is a more well-rounded way of eating, and a happier one too!