Last summer I was funded by the National Science Foundation to work at the University of Michigan Biological Station (UMBS) through a Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program. I like to think of this time as the beginning of my broad appreciation for entomology. This also was the time that I began to find host-parasite relationships so fascinating. In my research I calculated gregarine parasitism in the damselfly Calopteryx maculata (Beauvois, 1805) and attempted to correlate those findings with stream characteristics of the habitat in which they were caught. My paper, which I recently submitted to a small research journal, specifically focused on the idea that climate change will dramatically affect freshwater ecosystems, and therefore the interactions between the aquatic insect hosts and their parasites. My stream measurements included stream flow, dissolved oxygen, pH, and water temperature. That part of my research, though very interesting in its own right, is not the focus of this blog post. Gregarines are!

Gregarine parasites are one-celled protozoa that can be found within a variety of insect hosts. These parasites attach themselves to the gut epithelium of a odonate after ingestion through drinking water contaminated with oocytes or eating prey physically carrying these protists on their bodies. Once attached to the gut, gregarines absorb food ingested by the host. As other researchers have found, if a host contains a large number of gregarines, those parasites could restrict food and shorten the host’s lifespan.

After hearing of my research, István Mikó was interested in seeing some of these little guys up close and asked me on our last field outing to try and collect a few Calopteryx maculata (Beauvois, 1805). I don’t like to disappoint entomologists so I set out on my task. Luckily the site we went to in Whipple Dam State Park had a stream that had several! After collecting a few unlucky damselflies, it was back to the lab to dissect. I have included a picture of one male damselfly to honor his sacrifice to our research.

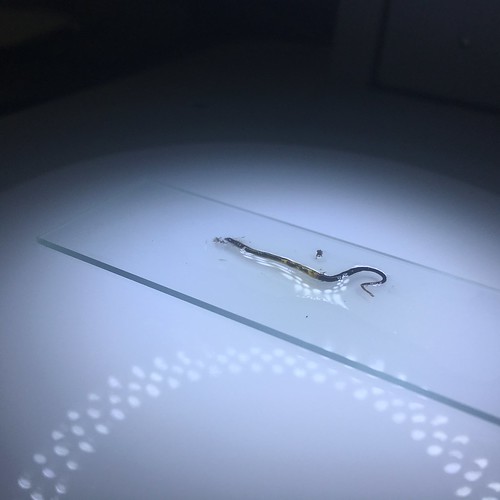

To dissect, we cut off the abdomen of the damselfly and carefully pull out the gut onto a glass slide with a small amount of distilled water. You can see the result of this in the picture below. Something to note about this picture is that you can actually see the protozoa with your naked eye! The small white flecks contained in the gut epithelium are the massive one-celled gregarines. It was no guarantee that this collecting site would have damselflies that hosted parasites but we got lucky!

István excitedly took the slide and began to set up the Frost’s imaging system for me. The pictures below are Brightfield images taken with an Olympus Compound Microscope.

Hopefully you can see how colossal these ONE-CELLED parasites can be! After counting these little guys on a rudimentary microscope last summer at UMBS this was an amazing experience and I hope you enjoy these high definition pictures as much as I did.