by Sandra Stelts, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Special Collections Library

The 2017 Charles W. Mann Jr. Lecture in the Book Arts was given March 30, 2017, by Professor Linda Tomko from the University of California at Riverside, on “Books, Bodies, and Circulations of Dancing in Early 18th-Century France and England” in Foster Auditorium. Photo by Nathan Valchar.

On Thursday, March 30, members of the Foster Auditorium audience found themselves immersed in the time and space of 18th-century stage sets, courts, ballrooms, and dance masters’ studios. We imagined ourselves in corsets and tri-cornered hats, humming tunes from the pages of books, all the while attempting to follow the pathways of the mysterious and, to us, unknowable patterns of lines known as dance notation.

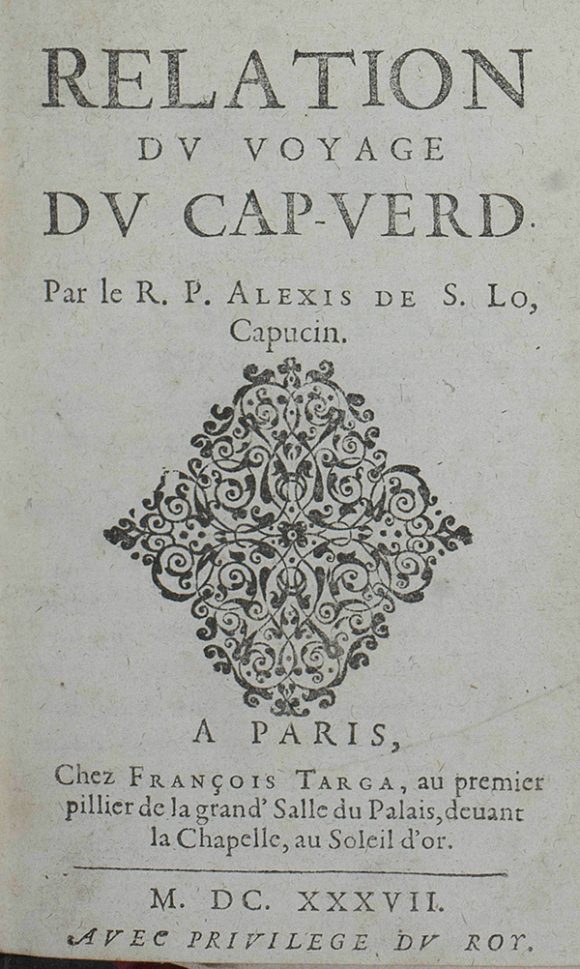

Linda Tomko used illustrations such as this one, from “The Art of Dancing Explained by Reading and Figures” by Kellom Tomlinson, London, 1735, considered to be one of the most beautiful of all dance notation books, in her talk for the 2017 Charles W. Mann Jr. Lecture.

Some notation systems are like tiny stick figures that depict gestures; others present an abstract beauty of their own, quite independent of the motion being described. Click on the image to view a high-resolution version in detail.This year’s Mann Lecture celebrated books found in Penn State’s Mary Ann O’Brian Malkin Early Dance Collection (1531–1804), which includes books on the history of European dance, its dancers (both amateur and professional), and on the development of dance notation—the visual dictionaries of dance elements. Systems of dance notation translate human movements into signs that permanently preserve the visual moment—a combination of flowing lines and disciplined gestures. Malkin herself often referred to these mystifying patterns as “chicken scratches,” and it was Tomko’s mission to enliven a number of examples of dance notation by occupying their space and literally “dancing by the book.”

In the 1680s, the ballet teacher Pierre Beauchamp invented a dance notation system for Baroque dancers. His system, known as the Beauchamp-Feuillet notation, was published in 1700 by his student, Raoul-Auger Feuillet, in 1700 as Chorégraphie; ou, l’art de décrire la dance (“Choreography; or, The Art of Describing the Dance”). The system spread rapidly throughout Europe, with English, German, and Spanish versions soon appearing. The notation became so popular at court and among the educated classes that books of collected dances were published annually.

Some notation systems are like tiny stick figures that depict gestures; others present an abstract beauty of their own, quite independent of the motion being described. Click on the image to view the detail in high resolution.

Tomko offered our audience an opportunity to reinvigorate the chicken scratches by first explaining and then demonstrating the intricate footwork and appropriate arm gestures represented in the notation. She guided us through the signs that indicated the steps used in the various dances, including which ones distinguished the male and female dancers. As a historian, dancer, and performer, Tomko is herself an embodier of dances past.

The Mann Lecture is an annual series that honors the late Charley Mann, the first head of the Department of Special Collections who served in that role for more than forty years. Beginning in 2002, the series has featured lively speakers and topics relating to the book arts, including printing, writing, illustration, and book design—anything that might be considered an aspect of the book arts, broadly construed. The series is a fitting tribute to Charley because such talks provide a vibrant forum to learn from the past, as well as a delightful reason to gather together people who share interests in books and bookmaking. The series is funded by the Mary Louise Krumrine Endowment.

We are already excited about the topic and speaker for next year’s Mann Lecture, and we hope you’ll make the series a regular appointment on your calendars.