Our generation was born into the digital generation. We were around when the first iPad and iPhone came out, grew-up learning how to be tech savvy and generally prefer technology over print sources. That being said, is there a difference between reading notes or textbooks in print than on a computer or our phones? Do we really learn better reading from print, or does it not matter in the long run?

Of course, there are some dangers and health concerns with reading on screens. These include computer vision syndrome, which is when you are on the computer for long periods of time and causes symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, strained and dry eyes, blurred vision, and neck and shoulder pain. Light from screens is also known to suppress the body’s production of melatonin, a hormone produced to help regulate sleep.

There have been countless studies on the effects that computer screens have on learning material. Most of these studies, such as this one and this one, came to the conclusion that we are not able to retain information from screens as well as we are able to retain information from print sources, citing the backlight of the computer as decreasing our concentration levels.

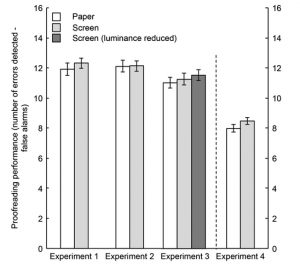

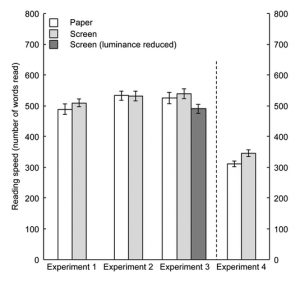

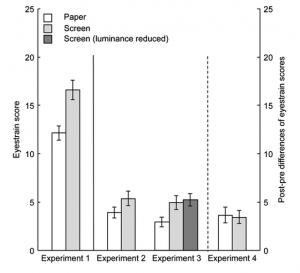

This study, though, came to the conclusion that reading from a computer is just as good as reading print, rejecting the null hypothesis. They conducted experiments with 615 altogether measuring proofreading skills on the computer and then in print. They measured the accuracy of proofreading on the computer an in print, the reading speed on the computer and in print and the eyestrain score. In each experiment the computer proved to be better or equal to the print in terms of their proofreading skills. The eyestrain scores were considerably lower for the computer readings than the readings done in print, as seen in the graphs below, which can be found in the link to the study.

As for the experimental design itself, there were pros and cons. The pro was that there were 615 participants, so the scope of the study was relatively large. While this many participants can’t obviously account for the whole population, it is larger than some studies in the past have been. As we have learned, large studies have a greater chance of yielding correct results. The con was that this experiment was neither a randomized or blind trial. There was no control group because each participant preformed both tasks of reading the online text (which would have been the experimental group) and the print text (which would have been the control group). Because the trial wasn’t blind, the participants knew what they were going to be tested for. This might have had an impact on the results because the participants might have subconsciously tried to do better on the computer than on the print because they knew what the null hypothesis was.

An article on Medical Daily listed some cons of reading on a screen. They said that we don’t generally take in as much information when we read online, accepting the same null hypothesis listed in the first two studies above, according to this study. Although there were only 72 participants in this study, it was a randomized control trial, unlike the previous study mentioned above, which might make it less prone to error. As mentioned in the second paragraph, looking at screens before you go to bed lessens your melatonin and takes longer for you to fall asleep. Medical Daily also did another article on how screens affect melatonin, here. It would be interesting to do a study to see if people who grew up using screens for the majority of their lives are less inclined to lose melatonin when they are using screens before bed because they might be immune to it.

Overall, it is still up in the air about whether we can learn better on screens or not, although most of the evidence points towards no, we can’t. Even if we can learn better on screens, there are so many side effects to constantly looking at a computer or cellphone that it might not be worth it in the long run.