When you reach for a glass of water which hand do you use? When you take a test, which hand do you use to bubble in your answers? Is it the same hand? Is it the opposite one? Do you ever give it a second thought? Though which hand you use for everyday tasks may seem simple in nature, there is a vast amount of science being done behind the scenes to see what it all means, and what it could mean for the future.

When you reach for a glass of water which hand do you use? When you take a test, which hand do you use to bubble in your answers? Is it the same hand? Is it the opposite one? Do you ever give it a second thought? Though which hand you use for everyday tasks may seem simple in nature, there is a vast amount of science being done behind the scenes to see what it all means, and what it could mean for the future.

To start, the American Psychological Association says that approximately 90 percent of the human population is right handed. Only about 1 percent of the human population is born ambidextrous. That also means that the other 9 percent are either left hand dominant or are mixed handed. Mixed handed refers to the idea that one hand is dominant for some tasks while the other hand is dominant for others. This is different from ambidexterity which is the ability to use either hand just as efficiently on any task. Unfortunately, there is currently no consensus in the scientific community on what handedness means, or how many classifications there should be for it. Indiana University recognizes this lack of standards throughout the scientific community. They go on to state that there is a clear difference between ambidextrous, and mixed handedness. So potentially, one can be right handed, left handed, cross dominant (mixed handed), or truly ambidextrous.

In an attempt to clear up some of the confusion, the Department of Psychiatry and Neurology at Tulane University performed a study that measured combinations of hand preference and hand performance to try to better classify groups of handedness. They studied 64 participants and found that more than 90 percent of the time, the hand you performed better with was the same hand you preferred or were more comfortable with. This study basically shows that handedness is not a clear-cut answer and that there is a spectrum of cross dominance between the two hands. This can be due to predetermined parts of the brain (nature), and which hand the person is forced to use at an early age (nurture).

On that note, one’s dominant hand is not determined from strictly nature or nurture but more of a combination of the two. Dana Smith, who has a Ph.D is psychology, reports that there are many genes known to be associated with handedness. So, when a child is born, they have a clear preference. Smith then goes on to say that this preference can try to be switched early on in a child’s life while he or she is still making neurological connections and pathways in the brain. When this happens, they become mixed handed and show signs of both the nature and nurture aspects of handedness.

On that note, one’s dominant hand is not determined from strictly nature or nurture but more of a combination of the two. Dana Smith, who has a Ph.D is psychology, reports that there are many genes known to be associated with handedness. So, when a child is born, they have a clear preference. Smith then goes on to say that this preference can try to be switched early on in a child’s life while he or she is still making neurological connections and pathways in the brain. When this happens, they become mixed handed and show signs of both the nature and nurture aspects of handedness.

So right about now you may be asking yourself, “Why does this matter?” It turns out there are many health and psychological problems that stem from handedness. Well, maybe not handedness, but more importantly brain lateralization. Brain lateralization is the idea that the brain has two hemispheres that compartmentalize and perform certain cognitive functions. For example, the left side of the brain is known to handle the use and understanding of language and speech. Though there seems to be correlation, the science is still not conclusive that right-handed people are left-brain dominant and left-handed people are right-brain dominant. However, through brain scans, we can determine which hemisphere is dominant on most humans. Once that is known, this leads to the knowledge of other things. For example, those who are left brain dominant tend to be better at analytical thinking while those that are right brain dominant tend to recognize patterns easier and have an easier time seeing the bigger picture to things.

However, there is a special breed of human that does not have an asymmetrical brain. Instead, they have brains that are much more symmetrical. This leads to the health and psychological problems I mentioned earlier. This breed of humans is the 1 percent: the ambidextrous.

The American Academy of Pediatrics published a study performed by Alina Rodriquez and other researchers that measured these health complications. Rodriquez measured 7871 children from Finland at the ages of 7-8 and again when they were 16. She found that at age 8, those who were ambidextrous were twice as likely to struggle with language skills and academics compared to those who were right handed. Also, at the age of 16, those who were ambidextrous were twice as likely to have these same struggles with school and language. They were also twice as likely to exhibit signs of ADHD compared to right-handers. And when comparing just the 16 year olds that were showing signs of ADHD, the ones who were ambidextrous seemed to have the more severe symptoms compared to those who were right handed.

Reflecting on this study, I would be wary to conclude anything about the whole human population based off of one study with one nationality of subjects. I would feel more comfortable if the study was repeated multiple times and used a broader group of individuals to sample. Also, the study mentions that the data they received was purely based on surveys distributed to people around the subjects like their parents and teachers. For one, parents may be hesitant to answer truthfully about whether or not their child has learning difficulties for various reasons such as pride or denial. That alone can introduce a level of bias. Furthermore, like I mentioned, these results are based off of surveys. Since no experimental variable was manipulated, this was not an experiment. That means there is no definite way of knowing handedness caused the increased numbers in health problems. The study is also not specific with its numbers. It is stated that those who are ambidextrous are twice as likely to have some of the psychological problems compared to right handers but do not provide a baseline risk. By only giving relative risk, it can be deceiving to those who read this study. For example, if 1 righty has ADHD and 2 ambidextrous children have ADHD, it is twice as likely. Not all statistically significant results are practically significant. .

Nonetheless, Rodriquez concluded from her study that her results could be due to “atypical cerebral asymmetry.” She also goes on to state that more research needs to be done on the biological mechanisms to this phenomenon. There is no clear answer as to what causes a brain to be symmetrical. There could be a third variable driving the relationship between brain lateralization and dexterity. If we can learn the connection between brain lateralization and handedness, we as a society can help pinpoint those who may be at risk of these health problems and give them the help they need without using invasive neurological procedures.

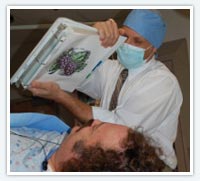

As of now, if one wants to know what hemispheres of the brain are specializing in certain tasks, a Wada test must be administered. A Wada test essentially hibernates one side of the brain so doctors can see what cognitive functions the side of the brain that is not hibernated is responsible for. This process can be costly and have health complications. The Department of Neurology at the Cleveland Clinic performed an analysis of 677 patients that had undergone the Wada test. A combined 10.9 percent experienced some type of health complication. 7.2 percent had encephalopathy, 1.2 percent had seizures, 0.6 percent had a stroke, 0.6 percent had transient ischemic attacks, 0.6 percent had a localized hemorrhage at the catheter insertion site, 0.4 percent had carotid artery dissections, 0.3 percent had an allergic reaction to contrast, and 0.1 percent experienced an infection.

As of now, if one wants to know what hemispheres of the brain are specializing in certain tasks, a Wada test must be administered. A Wada test essentially hibernates one side of the brain so doctors can see what cognitive functions the side of the brain that is not hibernated is responsible for. This process can be costly and have health complications. The Department of Neurology at the Cleveland Clinic performed an analysis of 677 patients that had undergone the Wada test. A combined 10.9 percent experienced some type of health complication. 7.2 percent had encephalopathy, 1.2 percent had seizures, 0.6 percent had a stroke, 0.6 percent had transient ischemic attacks, 0.6 percent had a localized hemorrhage at the catheter insertion site, 0.4 percent had carotid artery dissections, 0.3 percent had an allergic reaction to contrast, and 0.1 percent experienced an infection.

Handedness can be a way of knowing about one’s brain lateralization without using this invasive and expensive test. It would be amazing to see if just by running a few tests focused on hand dominance, we can know a plentitude about the functions of that individual’s brain. Science is getting better but it is imperative for more direct studies to be performed. The only way to be certain about anything is to prove causation through repeated experimentation. We know there are links between certain diseases like ADHD and ambidexterity and we know there is a relationship between ambidexterity and symmetrical brains, but how is this all connected? It is still unclear and maybe there is a third confounding variable that has yet to be discovered.

An experiment I would propose would be to manipulate several genes such as PCSK6 and LRRTM1, which are known to be associated with hand dominance, and see how they affect one’s chances of developing a known side affect to ambidexterity such as ADHD. Once we unlock the answer to this question, the possibilities for medicine and science are endless.

Photo URLs

“Don’t sit too close to the TV. You’ll ruin your eyes,” said every mom that ever existed. Since the 1960’s, parents all around the world have been telling their kids that sitting too close to a screen will cause them to go blind. This may be a myth. So why do parents continue to preach this possibly false claim to their kids? One reason is because of a little lie parents were telling that stuck around for too long, and the other is an error in the interpretation of causation. Lets see if there is any scientific evidence to suggest TV can

“Don’t sit too close to the TV. You’ll ruin your eyes,” said every mom that ever existed. Since the 1960’s, parents all around the world have been telling their kids that sitting too close to a screen will cause them to go blind. This may be a myth. So why do parents continue to preach this possibly false claim to their kids? One reason is because of a little lie parents were telling that stuck around for too long, and the other is an error in the interpretation of causation. Lets see if there is any scientific evidence to suggest TV can

To see if this theory even makes sense, I did some

To see if this theory even makes sense, I did some  This one experiment is not enough to convince me coffee naps definitely cause a greater reduction of sleepiness than coffee or a nap alone. I would like to propose a more focused experiment that would involve three groups. The first group would drink a 12-ounce cup of coffee plus take a 20-minute nap. The second group would drink a 12-ounce cup of coffee. The third group would take a 20-minute nap. I would want at least 30 people in each group, making for a total sample size of at least 90. Also, I would measure their brain activity before and after the treatments using a

This one experiment is not enough to convince me coffee naps definitely cause a greater reduction of sleepiness than coffee or a nap alone. I would like to propose a more focused experiment that would involve three groups. The first group would drink a 12-ounce cup of coffee plus take a 20-minute nap. The second group would drink a 12-ounce cup of coffee. The third group would take a 20-minute nap. I would want at least 30 people in each group, making for a total sample size of at least 90. Also, I would measure their brain activity before and after the treatments using a  “I love you.” These three words may be the solution to a problem that has existed for well over 100 years. Many believe drug addiction occurs because of chemicals in the drugs that have addictive properties. However, new evidence suggests that addiction is caused by our environment, not chemicals.

“I love you.” These three words may be the solution to a problem that has existed for well over 100 years. Many believe drug addiction occurs because of chemicals in the drugs that have addictive properties. However, new evidence suggests that addiction is caused by our environment, not chemicals. In many classic

In many classic

I am 18 years old and am already noticing that my hairline is beginning to recede. Granted, baldness runs in my family so maybe I should have seen this coming. Over 50 percent of men will have to deal with this problem by the time they are 50, and it can be quite demoralizing. So is there an answer to male pattern baldness? Medicine is good right now and it is getting better, but there still is no perfect cure. Right now, the best thing we can do is delay the balding process. Maybe a look at what researchers are currently testing will show us what needs to be discovered and where science must eventually progress to help solve this issue.

I am 18 years old and am already noticing that my hairline is beginning to recede. Granted, baldness runs in my family so maybe I should have seen this coming. Over 50 percent of men will have to deal with this problem by the time they are 50, and it can be quite demoralizing. So is there an answer to male pattern baldness? Medicine is good right now and it is getting better, but there still is no perfect cure. Right now, the best thing we can do is delay the balding process. Maybe a look at what researchers are currently testing will show us what needs to be discovered and where science must eventually progress to help solve this issue.

As I said before, it turns out that some stress is not harmful. Actually, short-term stress is showing signs of being very helpful to human’s immune health. Firdaus Dhabhar conducted a

As I said before, it turns out that some stress is not harmful. Actually, short-term stress is showing signs of being very helpful to human’s immune health. Firdaus Dhabhar conducted a  So what does this all mean? It means you may not want to listen to your relatives when they tell you all stress is bad. If you stress chronically, you may be at increased risks of becoming ill as Kiecolt-Glasser showed. However, if you stress a few hours before a big exam, or daunting lecture, you may just be increasing your odds of fighting off an attack to your immune system. The human body has a fight-or-flight response to stressful events for a reason. It is to help us. Not hurt us. It is not in your best interest to try to eliminate stress completely. Just keep it acute and not lasting months on end and you should not have to chalk your cold up to stress.

So what does this all mean? It means you may not want to listen to your relatives when they tell you all stress is bad. If you stress chronically, you may be at increased risks of becoming ill as Kiecolt-Glasser showed. However, if you stress a few hours before a big exam, or daunting lecture, you may just be increasing your odds of fighting off an attack to your immune system. The human body has a fight-or-flight response to stressful events for a reason. It is to help us. Not hurt us. It is not in your best interest to try to eliminate stress completely. Just keep it acute and not lasting months on end and you should not have to chalk your cold up to stress.