In my previous post “Human Sacrifice during Shang Dynasty“, I examined the historical background of renji (人祭 / ritual human sacrifice) practiced during Shang dynasty China (c. 1600 BC to 1046 BC). It is important to note that the kind of large-scale human sacrifice practiced by Shang rulers, though extraordinary, is not historically idiosyncratic. Human sacrifice rituals similar to that of renji were also found pre-Colombian Mesoamerica, most notably in Mayan and Aztec societies. [1] As scholars have already performed excellent analyses on the political economy of ritual human killings in Aztec empire (see, The Accursed Share by Georges Bataille), this post will focus only on large-scale human sacrifices as practiced in pre-Colombian Mayan society.

Human sacrifice rituals similar to that of renji were also practiced by the Mayans. To be sure, Mayan and Shang belief systems were quite different from one another, with each side embodying a heterogenous set of religious practices. For instance, monotheistic themes that were prevalent in Shang rituals are notably absent in Mayan mythos. Furthermore, in contrast with the abundant textual record from the Shang dynasty, much of the classical Mayan mythologies have been destroyed during the Spanish conquest, and the few surviving pre-Columbian Mayan written artifacts remain largely undeciphered. Nonetheless, when looking at mythical rituals in the specific form large scale human sacrifices, it is possible to delineate a relatively large set of common elements between the two otherwise distinct civilizations.

It is important to note that unlike the Shang, whose practice of ritual human sacrifice has long been well-established by historical records, human sacrifice in Mayan culture remained relatively unknown and received little scholarly attention until the late 20th century. Mayan human sacrifice only became widely studied after the 1970s, when archaeologists began to uncover large amount of new textual and archaeological evidence that shed light on Mayan sacrificial rituals. [2] Whereas the practice of ritual human sacrifice in pre-Colombian Mesoamerica was previously thought to be limited to the Aztec culture, whose imperial reign over the Valley of Mexico lasted from c.1400 AD to 1521 AD, it is now evident that such practice has been prevalent in Mayan culture centuries prior to that of Aztecs. [3] Current findings indicate that ritual human sacrifice has been continuously present in Mayan city-states throughout Yucatán regions [4] from the Classic period (c.200AD – c.900AD) up till the arrival of Spanish colonial forces in the 16th century. [5]

Also unlike the Shang dynasty, classical Mayan region has never been unified into a monolithic kingdom. Instead, Pre-Columbian era Mayan societies existed as multiple mutually independent city-states. [6] Classical Mayan city-states were organized around numerous densely-populated and sophistically developed urban areas. Those urban areas served as centers for politics, commerce and religion, and they were the sites where Mayan priest-kings performed human sacrifice ceremonies (see fig.2 & 3 below).

Similar to Shang, the Mayan human sacrifice were carefully organized and elaborately choreographed public spectacles. A detailed first-person account of the Mayan human sacrifice spectacle has been made by the 16th Century Spanish Catholic priest Diego de Landa, who conducted valuable early studies on Mayan religious practices during his tenure as the Bishop of Yucatán:

[quote]“When the day of the ceremony arrived, they [the sacrificial victims] assembled in the court of the temple; if they were to be pierced with arrows their bodies were stripped and anointed with blue, with a miter on the head. When they arrived before the demon, all the people went through a solemn dance with him around the wooden pillar, all with bows and arrows, and then dancing raised him upon it, tied him, all continuing to dance and took at him… If his heart was to be taken out, they conducted him with great display and concourse of people, painted blue and wearing his miter, and placed him on the rounded sacrificial stone. …then the falcon executioner came, with a flint knife in his hand, and with great skill made an incision between the ribs on the left side, below the nipple; then he plunged in his hand and like a ravenous tiger tore out the living heart, which he laid on a plate and gave to the priest; he then quickly went and anointed the faces of the idols with that fresh blood. At times they performed this sacrifice on the stone situated on the top step of the temple, and then they threw the dead body rolling down the steps, where it was taken by the attendants, was stripped completely of the skin save only on the hands and feet; then the priest, stripped, clothed himself with this skin and danced with the rest. This was a ceremony with them of great solemnity. The victims sacrificed in this manner were usually buried in the court of the temple…”[/quote] [7]

Although human sacrifice was of great political and religious importance in pre-Columbian Mayan societies, they were nonetheless performed as exceptional spectacles rather than everyday religious rituals. Similar to the case of the Shang, most Mayan religious sacrificial practices only involve non-human offerings such as animals. Ritual mass killings of human beings are reserved in only in two types of situations – the killing of enemy captives in victory celebrations, and the mass slaughtering of slaves in those rare “occasions of great tribulation” (such as severe drought or flood). [8]

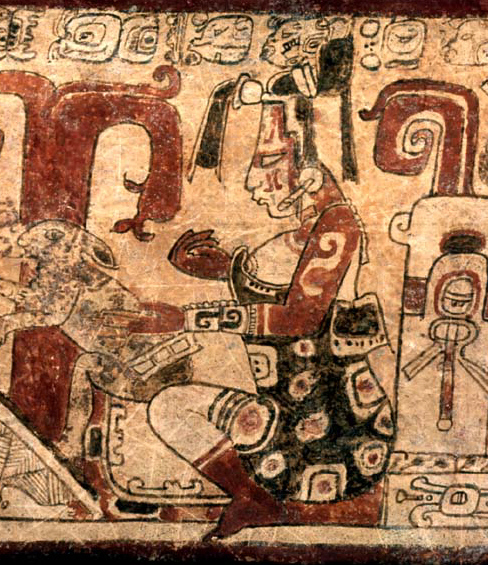

It is also important to note that for the most part of the Mayan history, the predominant technique used in their human sacrifice rituals is decapitation (see fig.4) [9] – possibly as reenactment of the Xibalba lords — rulers of the Mayan underworld — decapitating the legendary Mayan ancestor twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque (see fig.5 below). [10] [11] According to writings from Popol Vuh, the oldest surviving pre-Columbian Mayan mythology, the death of the legendary hero twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque gave birth to the maize god – the mythological signification of the Mayan staple crop. [12] The well-known “removing the heart” methods were only found to be commonly practiced during the later stages of Mayan civilization, possibly due to Aztecs influences. [13]

At this point, it might be appropriate to step briefly away from the minutiae of Shang and Mayan mythical practices, and instead look at the larger picture of human sacrifice. The practice of human sacrifice and ideas justifying these violent rituals mutually shapes and maintains one another. Even if violence is an inherent human condition, personal violent compulsions can only be transformed into collective rituals via collectively shared beliefs. Furthermore, it is important to note that effects of this dialectical relationship between sacrificial practices and their corresponding mythos are not contained within the sphere of religious life. Collective ideas, even in the form of “religious superstitions”, do not simply emerge from thin air ad libitum; rather, they both inflect and reflect human’s social and material conditions. Perhaps it is not too far of a stretch to consider human sacrifices in Shang and Mayan societies were not idiosyncratic incidents – but enduring repetitions of strictly regulated and carefully staged spectacles of ceremonial violence.

While arguing for explicit manipulative intentions on the part of Shang and Mayan rulers might run the risk of over-instrumentalizing and over-rationalizing their sacrificial practices, it is nonetheless difficult to overlook the powerful functioning of religious ritual in the maintenance of society, even without the presence of such explicit motives. [14] Given the amount specific features shared between the two separate and distinctly developed cultures in terms of their human sacrifice rituals, such idiosyncratic overlapping warrants further inquiry into the underlying conditions of the human sacrifices as practiced in Mayan and Shang societies. Given the lack of any known historical connection between Maya and Shang, I will seek in my subsequent posts to reinterpret the symbolicity of human sacrifice in those two societies within the context of their local political economies.

[divider]

Notes and References:

[1] See generally, Georges, Bataille, The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Zone Books, 1988). See also, Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina, “New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society,” Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology, (New York, U.S.: Springer, 2007). See also, generally, Diego de Landa, Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, tr. William Gates (New York: Dover Publications, 1937)

[2] See generally, Arthur Demarest, Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Forest Civilization, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

[3] Robert J. Sharer and Loa P. Traxler, The Ancient Maya, 6th ed (California: Stanford University Press, 2006). See also, Mary Miller and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. (London, 2003), introduction.

[4] The region includes present-day Yucatán Peninsula, Sierra Madre mountains, the Mexican state of Chiapas, Belize, and portions of Guatemala and El Salvador.

[5] Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina, New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatment in Ancient Maya Society, (Springer: 2007)

[6] Robert J. Sharer and Loa P. Traxler, The Ancient Maya, 6th ed (California: Stanford University Press, 2006). See also, Mary Miller and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. (London, 2003), introduction.

[7] Diego de Landa, Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, tr. William Gates (New York: Dover Publications, 1937), 51: “after a victory they cut off the jawbones from the dead, and hung them clean of flesh on their arms. In these wars they made great offerings of the spoils, and if they captured some renowned man they promptly sacrificed him, not to leave alive those who could later inflict injury upon them. The rest became captives of war in the power of those who took them.”

[8] Diego de Landa, Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, tr. William Gates (New York: Dover Publications, 1937), 48-51.

[9] Fig.5, HJPD, “Chichen Itza,Yucatan, Mexico: Ballcourt reliefs,” Wikimedia Commons, available: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AChichen_Itza_JuegoPelota_Relieve.jpg

[10] Robert J. Sharer and Loa P. Traxler, The Ancient Maya, 6th ed (California: Stanford University Press, 2006). See also, Susan D Gillespie, “Ballgames and Boundaries”. In Vernon Scarborough and David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame, (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1991), 317–345.

[11] Fig. 5 by Xjunajpù (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

[12] Coe, Michael D. “The Hero Twins: Myth and Image”. In Barbara Kerr and Justin Kerr ed. The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases, volume 1. (New York: Kerr Associates, 1989), 161–184.

[13] Sharer and Traxler (2006), 751.

[14] See, e.g., James Carey, “A Cultural Approach to Communication”: “A ritual view of communication is directed not toward the extension of messages in space but toward the maintenance of society in time; not the act of imparting information but the representation of shared beliefs.”

[box type=”note”]Fig.4, oracle bone inscription (Heiji 32035) “shall human blood be offered on the day of Xinyou? 辛酉其若亦氿伐”[/box]

[box type=”note”]Fig.4, oracle bone inscription (Heiji 32035) “shall human blood be offered on the day of Xinyou? 辛酉其若亦氿伐”[/box]