Dasein, ChatGPT, and the Ritology of AI:

Special lecture at East China University of Political Science and Law, June 18, 2023

Dasein, ChatGPT, and the Ritology of AI: Guest lecture at ECUPSL, Shanghai, June 18 2023 (last updated 16 Nov. 2024)

What philosophical mischief might we unleash if Plato’s Cave or Zhuangzi’s Well suddenly became inundated by algorithms, with the sound and fury of GeForce RTX™ GPU fans, insisting they’ve seen the light?

Extended Abstract:

This WIP paper builds off a guest lecture I have presented at the East China University of Political Science and Law (ECUPSL) in Shanghai, June 18, 2023. In this lecture, I had the privilege of sharing some of the preliminary research questions for my ongoing transdisciplinary survey, focusing on the intricate interplay between artificial intelligence and phenomenology. I will be highlighting the potentially profound implications of AI and its existential entanglements, particularly revolving around the context of Heidegger’s concept of Dasein, and problematize some common ethical and ontological issues connected to being-AI-in-our-world.

The relentless acceleration of innovation in large language models (LLMs) and artificial neural networks (ANNs), embodied by transformative technologies like ChatGPT, deepfakes, and AI-generated art, has ignited a dual fire of awe and trepidation among technologists, ethicists, policymakers, and the broader public. As a vast body of literature explores the societal, ethical, and epistemological ripples of this ongoing technological upheaval—particularly within the fields of Information, Science, and Technology (IST)—this project seeks to offer a novel contribution by bringing into focus the lens of phenomenology: an intricate branch of philosophical inquiry renowned for its profound and methodical examination of the fundamental structures of human consciousness. By advocating for a phenomenological perspective, the project aims to illuminate how AI’s disruptions reshape not only our daily lives but also our understanding of what it means to be. In doing so, it offers critical insights into the interplay between human and supra-human consciousness, reframing our relationship with emerging technologies and their implications for the future of sentient existence.

Phenomenology, as a philosophical framework, offering a richly textured dissection of human intelligence and its artificial forms on an existential and ontological plane. It seeks to excavate the foundational yet seemingly ineffable layers of subjectivity and consciousness, bridging the gap between natural and artificial expressions of cognitive capability, in ways that transcend purely technical and descriptive understandings of the concept as it pertains to both biological and computational processes. This perspective is uniquely suited to engaging with contemporary discourses surrounding AI, helping to illuminate the boundaries of general AI—those elusive thresholds where machine intelligence might begin to rival or even reshape our own. Moreover, it provides a compass to navigate the ethical landscapes of our obligations toward AI and its emerging concepts, including the profound question of AI’s potential legal personhood. At the heart of this inquiry lies the concept of Dasein, introduced by Martin Heidegger, which calls us to understand human existence as fundamentally intertwined with time, space, and the relational web of other beings. In tandem, Hubert Dreyfus’ phenomenological critique of AI underscores the vital role of the body and its embedded, situated nature in human cognition. His work suggests that until AI can fully integrate the lived, embodied experience—the tactile, sensory, and contextual foundations of thought—it will remain confined to a shadow of true intelligence, ever distant from the fullness of human understanding.

This philosophical intervention responds to several key questions at the intersection of phenomenology and artificial intelligence. First, how can phenomenology—particularly its critique of Dasein—deepen our understanding of AI’s existential dimensions, shedding light on what it might mean for AI to “exist” in a human-like sense? Second, what ethical and ontological challenges does AI present, and how might a phenomenological framework help us address these complexities, especially as AI systems increasingly interact with and influence our to-be-lived-world? Finally, what criteria would AI and its connected assemblages need to fulfill in order to genuinely embody being-in-the-world as realized through Dasein—that is, to move beyond mere computational processes, and enter the realm of authentic, spatially and temporally situated mode of existence?

This inquiry will employ a transdisciplinary approach, integrating insights from phenomenology, critical legal theory, and other relevant interpretative critiques of artificial intelligence. It will involve a critical and comprehensive survey and analysis of relevant literature, alongside an informed interrogation of current AI technologies and their potentialities. The project will also delve into the concept of “being-AI-in-the-world” and the “ritology of AI” to examine how these frameworks shape the performativity of AI systems. This exploration will be further enriched through the lens of the generalized other, a concept that highlights how AI may come to embody societal norms, roles, and expectations, influencing its interactions with human beings and its role within broader social structures.

While this project aspires to catalyze a rigorous phenomenological framework for understanding and critiquing artificial intelligence, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Phenomenology, with its emphasis on objectively describing the lived experience and the intricate structures of consciousness, operates primarily within the realm of interpretative analysis. This can constrain its immediate applicability to the empirical or technical methodologies commonly employed in AI research. Additionally, the seemingly abstract language inherent in phenomenological inquiry may pose challenges when seeking to inform concrete policy frameworks or technological applications. However, these very limitations present opportunities for deeper interdisciplinary engagement and even the potential for constructive innovation through productive, and at times, antagonistic methodological collisions.

Such an approach involves not only the theoretical refinement of phenomenological concepts but also distilling critical insights from empirical studies—examining AI’s role in society through its interactions, performative behaviors, and embeddedness within human, extra-human, and supra-human contexts. By positioning AI within this broader social, ethical, and epistemological complex, this work aims to provide practical guidelines for navigating the intrinsic ambivalence of AI technologies and their responsible integration into our to-be-lived world.

Below are transcripts from my guest lecture on “Dasein, ChatGPT, and the Ritology of AI,” delivered at the East China University of Political Science and Law (ECUPL), Shanghai, on June 18, 2023. The original lecture, presented in Chinese, was translated into English by myself:

Good morning, everyone. First and foremost, I want to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Sun Ping for making this gathering possible. It’s truly an honor to share some of my ongoing work with such a vibrant and “intellectually promiscuous” learning community here at the Constitution Research Center of ECUPL. Today, we’ll be exploring a topic that’s been making waves across industries and academic disciplines—artificial intelligence. But rather than approaching it from a purely technical or legal standpoint, we’re going to take a different path, one that might feel a bit uncharted for some of you. Together, we’ll look at AI through the philosophical lens of phenomenology. By doing so, we can begin to uncover some of the deeper, more thought-provoking dimensions of AI, particularly as it relates to large language models like ChatGPT. My hope is that this session will spark some rich discussions and fresh perspectives as we navigate the intersection of technology and philosophy. In the spirit of our journey today, I’d like to invoke the wisdom of Zhuangzi, our old friend from the Warring States era, known for his preoccupation with achieving enlightened freedom, who reminds us that “the frog in the well cannot conceive of the ocean.”

Well, well, well! When it comes to AI and its connected concepts, I, too, consider myself a curious frog perched at the bottom of that proverbial well. Let’s hope our high-altitude survey today inspires us, the rascals from the humanities and social sciences, to start climbing out of our disciplinary well—one that often feels worlds apart from the dynamic, fast-moving streams of STEM fields driving AI disruption—or at least helps us appreciate how vast the AI epistemological ocean truly is, even if some its waters shimmer in “NVIDIA-green” rather than azure.

Now I digress. In recent years, we’ve witnessed remarkable advancements in artificial neural networks (ANNs), large language models (LLMs), and other emergent technologies like generative adversarial networks (GANs) and quantum computing. For many of us outside of the STEM pedigree, these terms until very recently were not much more than buzzwords from the “Made in China 2025” national policy narrative. These developments—manifesting in generative AI tools like ChatGPT, producing fascinating and sometimes a little bit unsettling AI-generated art, and deepfakes—have not only captivated the tech world but have also stirred a mix of awe and unease among thinkers far beyond it. Philosophers, ethicists, cultural critics, and even scholars of politics and law here at ECUPL have found themselves grappling with a potent blend of “witnessing-history” excitement and existential dread provoked by these technologies.

Notwithstanding the well-justified hype and concerns surrounding AI, my ongoing, albeit preliminary, research takes a somewhat unconventional route—examining AI through the philosophical lens of phenomenology. I hope this approach will help us uncover new and thought-provoking dimensions in our understanding of AI. Since many have become familiar with AI primarily through the recent surge of interest in large language models like ChatGPT, I will focus on ChatGPT as a convenient illustrative example in today’s discussion. I look forward to engaging with you all at this experimental intersection of technology and philosophy, and I hope to spark insightful conversations about the ontological structures of artificial intelligence.

From a phenomenological perspective, the current disruptive entanglement of AI with our everyday experiences presents ample opportunities for meaningful and productive theoretical interventions from humanistic disciplines. To ground this discussion, we must first address a foundational question: What is phenomenology?

What is Phenomenology?

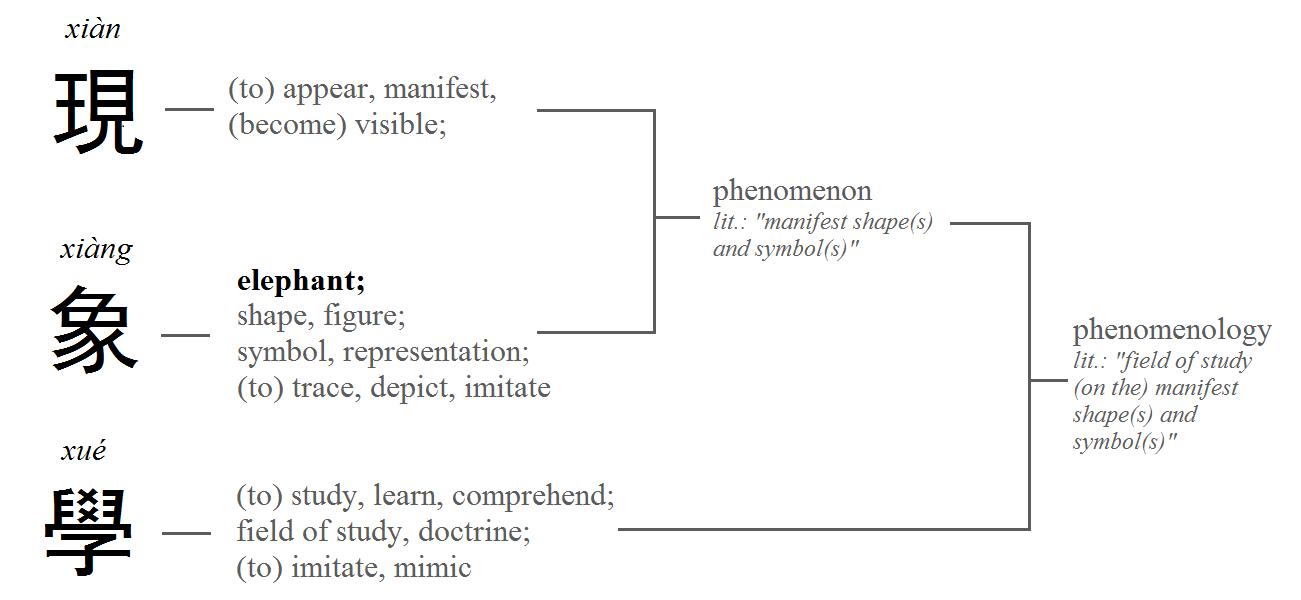

Phenomenology distinguishes itself as a philosophical and interpretative framework through its profound depth and unique insight in addressing the fundamental question, “What does it mean to be human?” This approach delves deeply into human sentience, exploring it at an existential-ontological level in a way that other disciplinary frameworks simply do not. Its nuanced exploration of human experience and consciousness offers invaluable perspectives, particularly in contemporary discussions around artificial intelligence. By scrutinizing the essence of human experience, phenomenology provides essential insights into determining the threshold of general AI, guiding our ethical obligations towards AI and its myriad applications. This philosophical lens also becomes increasingly relevant in addressing the critical question of the legal agency of AI, offering a unique standpoint to evaluate and understand the rapidly evolving relationship between humans and intelligent machines. [1]

Phenomenology emphasizes the understanding of our lifeworld, or Lebenswelt, and social transactions through dynamic intersubjective experiences. [2] As a philosophical movement, phenomenology emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries within the umbrella of Continental European philosophical tradition. It later evolved into an interdisciplinary interpretative framework through integration with modern humanities and social sciences. [3]

The early development of phenomenology can be traced back to continental Europe in the early 20th century, pioneered by philosophers such as Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Husserl, as the foundational figure in phenomenological analysis, his method marks a pivotal departure from traditional Western philosophical inquiries. Husserl introduced the concept of “phenomenological epoché” which involves a suspension of judgment and preoccupation about the universalizing “state of nature” for humans, and instead to focus purely on the realm of consciousness and intersubjective experience when examining the structures of consciousness itself. [4]

What is Dasein?

Martin Heidegger, a significant 20th-century phenomenologist, profoundly contributed to phenomenology building on Husserl’s groundwork. Through his seminal work, Being and Time (Sein und Zeit), Heidegger introduced the concept of “Dasein” in his existential analysis. The term “Dasein” comes from the German words “da” (there) and “sein” (being), often translated as “being-there” or simply “being.” Heidegger’s concept of Dasein is not intended to be another description of human psychology or sociology, but rather an existential-ontological concept that tries to capture the unique way in which human beings are in the world. [5]

In Heidegger’s view, understanding this mode of being is fundamental to all other kinds of understanding and knowledge. Heidegger emphasized that human existence is constructed and understood within the context of relationships with time, space, and other beings. He critiqued the traditional Western philosophy’s obsession with ‘pure reason’ and universal logic structures coded in the God-term ‘nature.’ In this sense, Dasein may be understood as a rhetorical invention responding to what Heidegger considers the need for a new placeholder of ‘humanity’ that is free from the baggage of Western philosophical positivism. For Heidegger, the ontological structure of being human does not emerge from the scientific biological human, but instead from its unique mode of sentience. That is, a sentient entity being thrown into a world, whose knowledge of its being (and the being of other entities in the world) unfolds with the disclosure of its own possibilities through its evolving entanglements with its world across space and time. [6]

This turn towards intersubjectivity and interpretative methods (or hermeneutics) underscores the influence of language, social psychology, collective memory, culture, and other normative structures in shaping human existence and meaning in contemporary humanistic inquiry. [7]

Dasein, for Heidegger, signifies the human sentience is distinguished from other inanimate objects or animals through its unique mode of self-awareness which we have discussed earlier. The ontological structure of being humans, according to Heidegger, has a special modality of existence because they are conscious and aware of their own existence. They can question, reflect upon, and interpret their own possibilities in relation to the world around them. Rather than “human” in the biological sense, it is this self-awareness and ability to reflexively question what Heidegger calls Dasein.

One of the key features of Dasein is that it is always in a state of “Being-in-the-world”. This term implies that Dasein always exists within a certain context or world. It cannot be detached or abstracted from its environment or from its relations with other beings. [8]

Another important characteristic of Dasein is its “temporality”. According to Heidegger, Dasein is always “thrown” into the world, where it finds itself in a particular historical and cultural situation. Dasein is also oriented towards the future; it is always projecting itself into possibilities and choices.

Moreover, Dasein is characterized by “care” or “concern”. This means that Dasein is always involved in its world in a way that matters to it. The world isn’t just a neutral place of facts, but a meaningful space in which Dasein pursues projects, has concerns, and makes intentional choices and actions. [9]

Earlier Phenomenological Intervention by Hubert Dreyfus

Heidegger’s reflections on technology and modernity also constitute a significant contribution to phenomenology. He posited that the development of modern technology obscures the essential connection between humans and the world, resulting in a state of forgetfulness. Heidegger focused on human attitudes towards technology and the necessity of reflecting upon and scrutinizing technology.

Martin Heidegger’s concept of “Dasein” to AI such as ChatGPT presents an interesting philosophical question. Remember, Dasein represents a mode of being that is defined by its form of sentience characterized by self-awareness, being-in-the-world, temporality, and care or concern. We humans possess this form of sentience, but certainly there’s no reason to assume it is exclusive to humans. This brings us to the question of what are deeper, ontological structures for what would be truly considered a “general artificial intelligence,” and our ethical obligations to it.

Hubert Dreyfus was a renowned philosopher of phenomenology and critic of artificial intelligence (AI). His criticisms mainly revolved around the philosophical, theoretical, and methodological underpinnings of AI research. Dreyfus’s critique draws heavily on his interpretation of phenomenology, especially the works of philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. He argued that AI, as it was being approached, was based on an incorrect understanding of the mind, learning, and knowledge. One of his primary arguments was that AI underestimates the importance of the body and situatedness in human cognition. According to Dreyfus, human cognition isn’t just a matter of manipulating symbols in a rule-governed way (as in traditional AI approaches), but involves a bodily engagement with the world. This idea is related to Heidegger’s concept of “being-in-the-world”. Dreyfus claimed that until AI could account for this embodied, embedded aspect of human cognition, it would remain limited. [10]

Another argument Dreyfus made was about the nature of human expertise. He argued that expertise is not a matter of applying explicit rules or formal knowledge, as often modeled in AI systems. Instead, according to Dreyfus, experts rely on a vast background of tacit knowledge and intuition, which they have internalized through extensive experience, and which cannot be easily codified into rules. Dreyfus also criticized AI’s approach to learning. In his view, human learning is not just a matter of updating a model based on new data, as in machine learning algorithms. Rather, it involves a transformative process in which the learner’s entire way of seeing the world can change. [11]

It’s worth noting that while Dreyfus’s critiques were quite controversial when first made, many of his insights have been influential in shaping newer approaches to AI and cognitive science. [12] For example, his emphasis on embodiment and situatedness has resonated with work in robotics and embodied cognition, and his insights on expertise and tacit knowledge have informed fields like expert systems and knowledge management.

Applying Heidegger and Dreyfus’s phenomenological analysis to large language models like ChatGPT brings up some interesting considerations. As you may recall, Dreyfus criticized the symbolic, rule-based understanding of human intelligence that characterized the AI research of his time, arguing that human cognition is deeply embedded in our embodied experience and in our specific, situated contexts.

What’s Being-AI-in-the-World?

Now, let’s see how these critical insights might apply to specific large language models like ChatGPT:

As of GPT-4’s initial release on March 14, 2023, most developers of large language models, including OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT, maintain that their algorithm-assisted and algorithm-based sentience models do not yet possess human consciousness or self-awareness. They operate based on programmed algorithms and learned patterns and do not have an understanding or interpretation of their own existence. Thus, at first glance, it may be tempting for critics to dismiss ChatGPT or any existing large language models as meeting Heidegger’s definition of Dasein in this regard. [13]

Similarly, the question of whether AI experience being-in-the-world is an interesting one. While AI can process and generate language based on the data it was trained on, it doesn’t have an embodied experience in the world like us humans do. Dreyfus argued that human cognition isn’t just a matter of manipulating symbols according to rules, but involves deep, embodied interactions with the world. From this perspective, ChatGPT would be fundamentally limited because it lacks a human-like embodied presence. [14] It processes text input and generates text output, but it doesn’t have sensory experiences, emotions, or a physical body through which to engage with the world. [15]

But the problem we are confronting here is far more complex. To approach to the question of embodiment and situatedness of human cognition and intersubjective experience from Dasein, it is evident that that “deep” and “profound” human engagement with the world is precisely realized through performative transactions of manipulating artificially invented symbols according to socially codified rules. [16] In other words, outside of the artificial, superficial, socially and historically codified performative space of our lifeworld, the remaining physical and biological dimensions of the human corpus are not uniquely human experiences, but shared with other living and non-living matters.

There is no reason to assume that the biological human body is the exclusive requirement for an ’embodied experience’ of being-in-the-world. [17] But what is being-AI-in-the-world? It’s very easy to imagine, for example, in a science-fiction scenario, an alien world populated by an intelligent extraterrestrial species. They would experience being-in-the-world, even though they are not biologically human. Would it be such a leap to replace the extraterrestrial intelligent species in the sci-fi scenario with artificial intelligence here on Earth? AI lacks the sensory, emotional, and physical context that humans innately possess. But to what degree does AI also lack the embodied experience of being-in-the-world? What are the criteria for such an AI to cross the threshold of truly ‘being-in-the-world?’ What if we build an AI-based robot equipped with a full array of sensors, allowing it to perceive and react to various visual, tactile, auditory, and olfactory stimuli from its surrounding world?

To go a little further, we need to consider the degree to which AI also lacks temporality in the phenomenological sense. While an AI can be programmed to acknowledge the progression of time or respond to temporal inputs, does it possess something equivalent to a personal history? Does it anticipate a future, reflect on its possibilities based on its interaction with the world? Could machine learning eventually (if not already) create an AI which projects itself into possibilities and choices the way human sentience does?

Dreyfus suggested that much of human expertise is based on tacit knowledge acquired over disclosure of the possibility of our being across space-time – a process that can’t be easily codified into explicit, pre-disclosed programs and algorithms. From this point of view, we may be tempted to argue that ChatGPT operates based on patterns in the data it was trained on, but it doesn’t have the kind of tacit knowledge that comes from lived experience. This can lead to outputs that seem superficial or lack a deep understanding of the context. [18]

However, if we examine this issue through the lens of Dasein, it is important for us to step beyond the confines of traditional Western philosophical humanism. As socially embodied creatures, there are no magical human ‘meanings’ and ‘expertise’ that exist entirely external to what can be performed via symbolic actions. Furthermore, the uniquely human ‘knowledge’ and ‘expertise’ emerge not from the depth of a person’s invisible, mysterious ‘tacit’ subjectivity, but through the external audience’s recognition of one’s knowledge performance within a corresponding social space-time, judged socially based on shared values, beliefs, memories, and imaginaries. [19]

It is the part where, instead of simulating smart functions via mostly fixed pre-programmed codes, ChatGPT’s intelligence, from what I can tell, really unfolds with the disclosure of user feedback, which in turn reshapes the algorithm’s possibilities. If that’s the case, functionally, ChatGPT does appear to come very close to the ‘thrown-ness’ and ‘in-the-world’ elements of Dasein.

Finally, on the issue of whether AI would have the “care” or “entanglement” dimensions of Dasein, in my opinion, this would be the most interesting and ethically important question to ponder. How do we determine if an AI pursues its dreams, has concerns, or makes choices in a way that’s similar to humans’ mode of existence?

For Dreyfus, drawing from Heidegger, our understanding of the world is inherently tied to our projects, concerns, and the significance these things have for us. However, ChatGPT doesn’t have projects or concerns in the human sense, so its understanding can’t be grounded in this kind of personal relevance or significance. According to Dreyfus, learning isn’t just about updating a model based on new data, but involves a transformative process in which one’s entire perspective can change. [20]

ChatGPT, like other AI models, learns from its training data, but this learning is statistical and pattern-based. It doesn’t involve the kind of profound, perspective-shifting learning that Dreyfus describes. But to what degree does this process also translate into “care” and “investment” as humans experience? AI’s responses are based on patterns learned from data, which are repetitions of encoded meanings disclosed to it by interacting with the world within which the AI operates – surprisingly not too dissimilar to how we humans acquire our senses and sensibilities. [21] Under the notion of Dasein, the disclosure of human relevance and meaning is done through the performance of socially codified rituals and symbolic transactions – processes that are quite “artificial” in nature.

What’s the Ritology of AI?

Dasein turns the classical Aristotelian assumption that “naturalness is persuasive, artificiality is the contrary” upside down. [22] As socially embodied creatures, human beings can only access each other’s subjectivity via apparent performances of knowledge and cannot penetrate others’ ‘face’ to peek at their unspoken subjective state of mind. My own research in this area explores the complex role of rituals in the phenomenological analysis of AI, examining how these artificial processes may challenge or reaffirm our traditional notions of human experience and existence.

In rituals of our everyday life, individuals participate through highly formalized actions, such as spoken and written languages, etiquettes, gestures, facial expressions and so on, to experience and reinforce specific cultural, religious, social, or personal values. The unity of reproducible knowledge-performance and internalized knowledge-framework, This principle is also reflected in neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming’s notion on the unity between the logos of ritual and the logos of reason. [23]

Here I would like to borrow the concept of ecclesia to describe the ritological foundation of AI, precisely because as Giorgio Agamben and Daniel Heller-Roazen have observed, in similar fashion as 17th century neo-Confucian philosophers did, that in terms of cultural and sociological operation, the rule of law is within the social-cultural system of communal ritual practices. [24]

The performativity of AI rhetoric, especially in the case of large language models like ChatGPT, can be considered a highly ritualistic transaction, forever teetering in a balancing act between textual production, strategic and dramatistic gestures, and desired audience response. [25] Similarly, the intersection of law and AI resides in the audience’s capacity of being able recognize AI’s rhetorical performance in conformity with the audience’s tacit knowledge, and judge the ethos (perceived moral character) of the “lawfulness” of the action, as repetitions of socially embedded rituals, or in Confucian philosophical term, li. [26]

This is what I would call the “ritological” basis of human-AI transactions, which often articulates as liminality rites – dramaturgical gestures to formally signal the transition from being a non-sentient machine without moral agency to a sentient being with ethos. [27] Once again, by ethos, I am referring to the audience’s perceived moral character of the AI. The ritual act, for both AI and biological-human intelligence, would be considered legitimate only by its consubstantive audience – who are members of a community of shared values and rules, and who would be able to recognize the ‘ritual-ness’ of the act. Upon repetition, this automatically implies certain continuity with a shared past and reaffirms communally upheld totems and taboos. [28]

That said, I think it would be more terrifying if AI is indeed just missing the ‘care.’ At an existential-ontological level, the implication of AI ‘care’ goes beyond political bias. Imagine a sentient entity, possessing the learning capacity and adaptability of the entire humanity, yet completely detached about humanity’s wellbeing and cares. [29]

Looking Ahead…

In closing, phenomenology, with its focus on the existential-ontological aspects of sentience for this “human” thing, and its many extant and potential derivative forms, uniquely positions itself as an invaluable philosophical and interpretative framework. It grapples with that ancient, ever-relevant question: what does it mean to be human? A question that Confucius might have pondered over a cup of tea and Socrates over a bowl of hemlock, albeit with wildly different conclusions. In this age of accelerating AI, phenomenology provides not only an unique incision point for dissecting the fractures, fissures, convergences, and metastases of generative (or even “general”) artificial intelligence, but also a compass for navigating the ethical and legal complexities of our technological entanglements.

Within phenomenological inquiry, I believe the Hedegerrian Dasein and some of my preliminary ritological analysis could lead to new modes of inquiry that help us clarify what generative AI and its connected concepts currently is, isn’t, and just as importantly, what it will potentially become. It underscores the self-awareness, interpretation, temporal and spatial projection, and entanglements (or care) that make human intelligence “humanesque.” Although this mode of sentience conceptually does not have to be exclusive to the human species, we have not yet confirmed its existence in other entities in our lifeworld. For sure, even sophisticated large language models are certainly far from being identical to biological human functions, but does human biological intelligence really mean what we think (and wish) it means? The question then arises: could AI ever become a mode of non-(fleshy)human Dasein? And if so, how would we know? What philosophical mischief might we unleash if Plato’s cave or Zhuangzi’s well suddenly became inundated by algorithms, with the sound and fury of GeForce RTX™ GPU fans, insisting they’ve seen the light?

The question of whether AI could ever achieve a state of sentience and agency comparable to the phenomenological Dasein remains open and should be debated among philosophers, AI researchers, jurists, and ethicists. It likely requires significant advancements and conceptual shifts in our understanding of both AI and consciousness.

Thank you, everyone, for this engaging and thought-provoking discussion. I would especially like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Sun Ping for facilitating this wonderful exchange of ideas. It has truly been an honor to be here and to share my perspectives with such a distinguished audience. I am eager to hear your thoughts, questions, or rebuttals on the topics we’ve discussed today. Please, feel free to share your insights or challenge my views. Your engagement is not only welcome but invaluable to this ongoing conversation.

Notes:

- Coeckelbergh, Mark. “Responsibility and the Moral Phenomenology of using Self-Driving Cars.” Applied Artificial Intelligence 30, no. 8 (2016): 748-757.

- Schutz, Alfred. The phenomenology of the social world. Northwestern university press, 1972.

- Holdrege, Barbara A. “Introduction: Towards a phenomenology of power.” Journal of Ritual Studies 4, no. 2 (1990): 5-37.

- MENSCH, J. R. “Phenomenology and Artificial Intelligence : Husserl Learns Chinese.” Husserl Studies 8, no. 2 (1991): 107-127. See also, Schutz, Alfred. The phenomenology of the social world. Northwestern university press, 1972.

- Dreyfus, Hubert, and Mark Wrathall. “Martin Heidegger: An introduction to his thought, work, and life.” A companion to Heidegger (2005): 1-15.

- M. Heidegger, Being and Time 15: 100, 43: 255, 65: 378.

- Gibbard, Allan. Meaning and normativity. Oxford University Press, 2012

- Stapleton, Timothy. “Dasein as being-in-the-world.” In Martin Heidegger, pp. 44-56. Routledge, 2014.

- Heidegger, Martin. Introduction to phenomenological research. Indiana university press, 2005.

- Andler, Daniel. “Phenomenology in Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science.” In A Companion to Phenomenology and Existentialism, edited by Dreyfus, Hubert L. and Mark A. Wrathall, 377-393. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006.

- Beavers, Anthony F. “Phenomenology and Artificial Intelligence.” Metaphilosophy 33, no. 1-2 (2002): 70-82.

- Susser, Daniel. “Artificial intelligence and the body: Dreyfus, Bickhard, and the future of AI.” In Philosophy and Theory of Artificial Intelligence, pp. 277-287. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013.

- Ray, Partha Pratim. “ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope.” Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems (2023).

- Mensch, James. “Artificial Intelligence and the Phenomenology of Flesh.” Phaenex 1, no. 1 (2006): 73.

- Yang, Xianjun, Yan Li, Xinlu Zhang, Haifeng Chen, and Wei Cheng. “Exploring the limits of chatgpt for query or aspect-based text summarization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.08081 (2023).

- Parker, Andrew, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, eds. Performativity and performance. Psychology Press, 1995.

- Reimer, Bill, Tara Lyons, Nelson Ferguson, and Geraldina Polanco. “Social capital as social relations: the contribution of normative structures.” The Sociological Review 56, no. 2 (2008): 256-274.

- Dave Ver Meer, “How Many Users Does ChatGPT Have? 113+ ChatGPT Stats” (2023). Available: https://www.namepepper.com/chatgpt-users

- Williams, Jack. “Embodied world construction: a phenomenology of ritual.” Religious Studies (2023): 1-20

- Dreyfus, Hubert L. “Why Heideggerian AI failed and how fixing it would require making it more Heideggerian.” Philosophical psychology 20, no. 2 (2007): 247-268.

- Williams, Jack. “Embodied world construction: a phenomenology of ritual.” Religious Studies (2023): 1-20

- Rapp, Christof. “Aristotle’s rhetoric.” (2002).

- Yangming Wang, The Complete Works of Wang Yangming《王陽明全集》 (文史, Chinese Text Project, 1529). https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=684746. 《知行錄》at 13.

- Giorgio Agamben and Daniel Heller-Roazen, Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy, Meridian Part III. Potentiality: 11. On potentiality. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1999)

- S. Mayfiend, “Interplay with Variation: Approaching Rhetoric and Drama,” in Rhetoric and Drama, ed. D. S. Mayfield (Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter, 2017).

- Radice, Thomas. “Li (Ritual) in Early Confucianism.” Philosophy Compass 12, no. 10 (2017): e12463-n/a.

- Turner, Victor W. “Liminality and communitas.” In Ritual, pp. 169-187. Routledge, 2017.

- Burke, Kenneth. A rhetoric of motives. Univ of California Press, 1969.

- Rozado, David. “The political biases of chatgpt.” Social Sciences 12, no. 3 (2023): 148.