originally posted by Keren Wang, July 20th 2015

For this research project, in collaboration with Professor Stephen Browne from Penn State University, we seek to investigate New York City, circa 1789 through the five senses: what did it look like, sound like, smell like, taste like, and feel like? I will be primarily focusing on looking directly into relevant sources from the early years of the Republic: newspapers clippings, personal diaries, musical scores, travelers’ accounts, correspondence, menu offerings, historical art, architecture, music, theater, food, etc. By the end of this project, hopefully we may find ourselves with a collection of blog posts, nicely crammed with contemporary accounts of life in the City as it was lived bodily, publicly, and culturally.

Here in part 1, I will begin on how the city looked at a “macro-level”. Here are some of the findings that may help us get a general sense of the topography and city-planning of NYC during late 18th to early 19th century:

First let’s look at some of the topographic pretext of New York during the early years of European settlement. This map below (retrieved from the New York Public Library Digital Collections [1]), published in 1635 by the famous Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu depicts Hudson River Valley and its surrounding area during the early years of Dutch colonial settlement in the area. This map was based on the surveys conducted by Dutch traders Adriaen Block, whose 1611-1614 expeditions have yielded detailed geographical information on the present-day North American continent between 38th parallel and 45th parallel.

Figure 1: 1635 Bleau map, “Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova” (Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library)

Note that Long Island (labeled “Matouwacs”) is located near the center of this map. To the right of Long Island is “Nieu Amsterdam” (New Amsterdam), which is the first permanent European settlement on the present-day Manhattan island. Several other place names labeled by this map are still in use today, such as “Manatthans” (Manhattan), and “Hellegat” (Hell Gate). [2] The 1635 Bleau map depicts the Hudson Valley region as heavily forested, with several Native American settlements demarcated along the Hudson River.

The map drawing in figure 2, made in 1660, depicts the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam on the Manhattan Island during mid 17th century. This map is among the very few topographical documents that have survived from the period of the Dutch colonial rule of New York. [3] Note that the star-shaped bastion, “Fort Amsterdam”, is located near the tip of the Manhattan Island on this map. Additionally, the settlement is enclosed by a defensive wall structure that runs continuously through the northern and western borders of the city. These defensive structures resemble typical features of medieval European “walled-cities” (see map of the Dutch city of Haarlem, circa 1550 for comparison).

Figure 2: 1660 map of New Armsterdam, “Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederlandt” (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

While the 17th century New Amsterdam bares little resemblance to New York City today, it is important to note that traces of many topographic features from from that era can still be discerned from the present day cityscape:

Figure 3: 2015 map of the southern tip of Manhattan Island (provided by Google Map)

Note that contemporary street grid in the southern tip of Manhattan Island (see figure 3) still roughly follows the general pattern established by New Amsterdam more than 350 years ago. Also note the location of the West Street (route 9A) in the 2015 map below overlaps with that unnamed broad avenue north of Fort Amsterdam from the 1660 map.

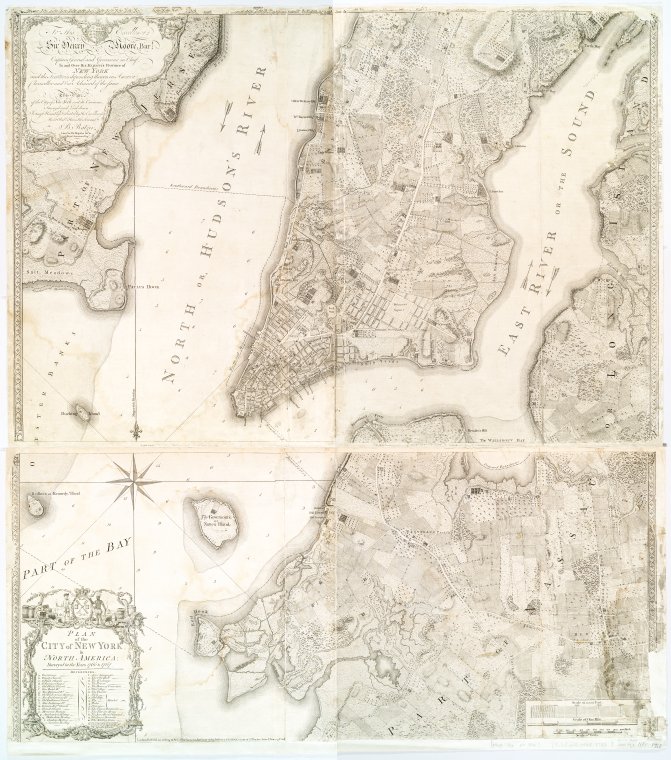

The cityscape of New York under British colonial rule remained mostly confined within the southern tip of Manhattan Island. Figure 4 below is an extremely detailed map by British cartographer Bernard Ratzer depicting the City of New York and its surrounding region, based on survey data gathered between 1766-1767. [4] The upper-left corner of the map includes dedication from to “His Excellency Sir Henry Moore, Bart., captain general and governour in chief, in and over His Majesty’s Province of New York and the territories depending thereon.” The Ratzer map depicts a rather “rural” landscape of the region — with a relatively small urban area located at the southernmost portion of Manhattan; and the rest of the Manhattan Island, along with present day Brooklyn and Queens were mostly covered with plantations, marshes and woodlands.

Figure 4: “Plan of the city of New York in North America : surveyed in the years 1766 & 1767” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Now let’s take a look this 1797 map drawing (fig.4) of the same area, appropriately titled “A New and Accurate Plan of the City of New York” According to the New York Society Library Collection, this print is among the “most accurate ad beautiful engraved plans of the city” surviving from the early years of U.S. independence [5] :

Figure 5: “A New & Accurate Plan of the City of New York in the State of New York in North America.” Published in 1797. New York Society Library

This map depicts the extend of the built-up city areas as of 1797 in shaded blocks — occupying similar areas as shown in the 1767 Ratzer map. However, the 1797 map depicts a considerably different vision of city-planning to the Ratzer map. As shown in the map above, to the north of the developed urban areas are those neatly-organized street grids planned for the future expansion of the city, known as the “Taylor-Roberts Plan”. In comparison with the 1660 map, both Ratzer map (fig.4) and this 1797 map look remarkably more “modern” — in addition to improved geographical accuracy, those individually drawn houses and gardens shown in the 1660 map have been abstracted into differently shaded “land use zones” in the 18th century renditions. In contrast to the “walled-in” layout of New Amsterdam that’s reminiscent of medieval forts, the 1797 map reflects a much more “open” and expansive city plan. Those defensive city walled that once defined and confined the physical extend of New Amsterdam have been replaced with vast swaths of “to-be-occupied” rectangular plots. The shift of New York city topography between mid-17th and late-18th centuries suggest change in the function of the city from being a defensive stronghold to a hub of economic growth and expansion.

The kind of expansive grid-style city planning from the 1797 Taylor-Roberts Plan continued into the early 19th century New York. The map shown in Fig. 6 & 7 below depicts the bold 1807 “Commissioner’s Plan” for developing the entire Manhattan Island:

Figures 6 & 7: “A Map of the City of New York by the Commissioner Appointed by an Act of the Legislature Passed. April 3rd 1807”. New York Society Library.

The survey for the map shown above was made in accordance with the provisions of a 1807 legislation titled “An Act relative to Improvements, touching the laying out out of Streets and Roads in the City of New York, and for other purposes”. The Act appointed Governeur Morris (then U.S. Senator from New York), Simeon De Witt (Surveyor General of New York), and John Rutherfurd (U.S. Senator from New Jersey) as Commissioners of Streets and Roads in the City of New York between 1807 – 1811, with “exclusive power to lay out streets, roads and public squares… as to them shall seem most conductive to public good.”

Notes and References:

[1] Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 11, 2015. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-eea1-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

[2] Benjamin Schmidt, “Mapping an Empire: Cartographic and Colonial Rivalry in Seventeenth-Century Dutch and English North America,” The William and Mary Quarterly , 3rd Series, Vol. LIV, No. 3 (July, 1997), 549-578.

[3] The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederlandt.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 11, 2015. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c0b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

[4] Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Plan of the city of New York in North America : surveyed in the years 1766 & 1767” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 21, 2015. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8bd31a8f-cfed-3cb6-e040-e00a18061cd0

[5] The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909: Print Collection, plate 79. “A New & Accurate Plan of the City of New York in the State of New York in North America.” Published in 1797. New York Society Library. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

You must be logged in to post a comment.