The ritual taking of things that are of human value, including the ritual killing of humans, has been continuously practiced for as long as human civilization itself has existed. In my presentation for the upcoming virtual 2020 National Communication Association’s Annual Convention, I will highlight key findings from one of my ongoing historical archival projects, focusing on the rhetoric of human sacrifice as represented in Early Bronze Age China oracle bone scripts (c.1250 BC – 1046 BC). It will be delivered at the virtual paper session, “GPS: Changing Routes in Rhetoric’s History” sponsored by the American Society for the History of Rhetoric on November 1st, 2020.

In this presentation, I will visually highlight and analyze a broad collection of examples of oracle bone inscriptions on ritual human sacrifice from the mid to late-Shang period. The purpose of this presentation is to provide better understanding on the logographic invention and legitimation of violent state practices during Early Bronze Age China. Specifically, my archival investigation found that Shang rulers framed human sacrifice as prayers to the Shang high deity, Shang-Di, to deliver their people from major calamity. State sacrificial ceremonies involving the killing of humans appear to be restricted, as least in writing, to exceptional occasions of severe food shortage and the aftermath of a major military conflict. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of war captives and/or slaves are said to be executed during these apotropaic ceremonies via means of decapitation, burning and/or bloodletting.

Although people in modern society seldom consider ritual sacrifice (especially those that involve the slaughter of humans for ritual purposes) as an ongoing practice, it nonetheless remains an organizing element of contemporary institutions of governance. Capital punishment, for instance, is one of the oldest forms of human ritual sacrifice that is continuously practiced to the present day.

René Girard observed in his Religion and Ritual, “sacrifice is the most critical and fundamental rites…all systems that give structure to human society have been generated from it: language, kinship system, taboos, codes of etiquette, patterns of exchanged, rites, and civil instructions.” American social psychologist Erich Fromm further noted, in The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, that not only does the religious phenomenon of sacrifice still exist in modern society, but modernity has in many ways amplified the scope, intensity and destructiveness of ritual human sacrifice.

One of earliest, and most well-documented examples of institutionalized, large-scale human sacrifice regime is found in oracle bone scripts unearthed from mid to late-Shang period (c.1250 BC – 1046 BC) archaeological sites in China. Written artifacts excavated from late-Shang archaeological sites were predominantly in the form of oracle bone script. These writings were used specifically during state divination ceremonies where the Shang ruler, both acting as a king and as a high priest, would carve scripts concerning matters of state importance (such as military affairs, prayers for bountiful harvest, and matters concerning sacrificial offerings) onto specially prepared tortoise carapaces and bovine bones.

Oracle bone script is among the earliest known fully developed Chinese writing systems. Despite its age, the oracle bone script is nonetheless a highly developed iconographic form of writing, which is partially mutually intelligible with contemporary Chinese characters, and shares similar syntactical framework with classical written Chinese. Thus, despite its ancient origin, the oracle script is accessible to modern day readers, perhaps due to the fact that it is, like contemporary Chinese, a purely logographic medium that transmits meaning without relying on phonetic representation, and therefore has remained relatively static across millennia.

A sizable portion of the oracle bones uncovered in Shang archaeological sites contain inscriptions, known as oracle bone scripts, specifically concerning ritual human sacrifices performed by the Shang ruling class. These written records are also corroborated by the discovery of numerous mass-graves of human sacrifice victims in these sites.

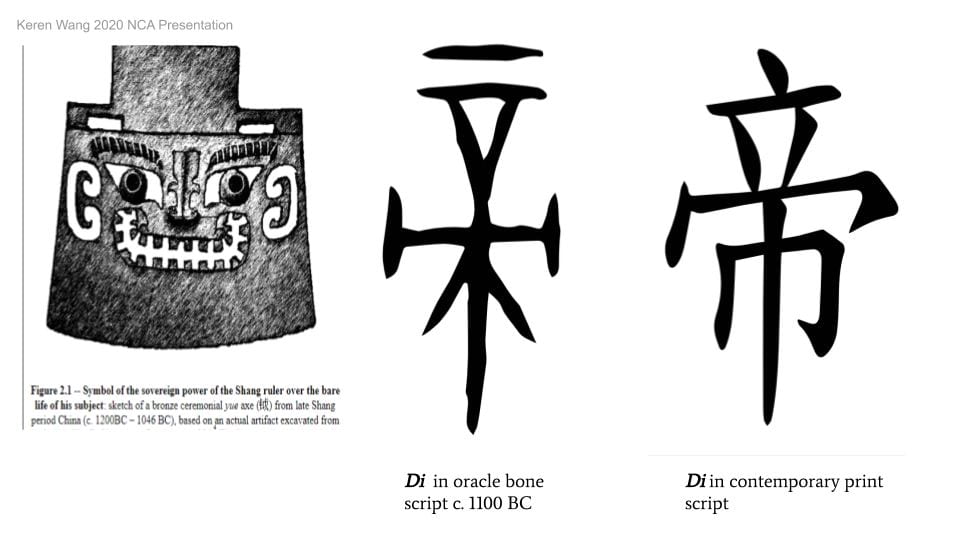

According to official historical records compiled during the Zhou dynasty (1046 BC–256 BC), Shang was the second Chinese dynasty preceded by the quasi-legendary Xia dynasty (c.2070 BC –1600 BC). However, as there are no conclusive archaeological records proving the existence of the Xia dynasty, Shang is the earliest confirmed Chinese dynasty in that the earliest written records were dated to this era. Written artifacts excavated from Shang archaeological sites were predominantly in the form of oracle bone script. These writings were used specifically during state divination ceremonies where the Shang ruler, both acting as a king and as a high priest, would carve scripts concerning matters of state importance (such as military affairs, prayers for bountiful harvest, and matters concerning sacrificial offerings) onto specially prepared tortoise carapaces and cow bones. The Shang king (Di) would then prod the oracle bones with a red-hot bronze rod, which would cause the bones to crack under the intense heat, indicating that the singular supreme deity of the Shang people, Shang-Di (上帝, lit.: “supreme high Lord”) had answered the questions inscribed on the bones, and the cracks left on the bones were supposedly Shang-Di’s divine answers. Only the Shang king could interpret these and announce them to his people as divine mandates.

A sizable portion of the oracle bones uncovered in Shang archaeological sites contain inscriptions, known as oracle bone scripts, specifically concerning ritual human sacrifices performed by the Shang ruling class. These written records are also corroborated by the discovery of numerous mass-graves of human sacrifice victims in these sites. In most Shang sacrificial rituals, only animals, and valuable chattels (such as bronze wares) would be used as offerings. There were only two exceptional circumstances where human sacrifices were made: xunzang 殉葬 and renji 人祭. Xunzang 殉葬 (lit. “suicide burial”) refers to the practice in which personal slaves and servants of Shang king, upon the death or their master, were expected to “volunteer” themselves to be buried alive as a form of “honor suicide.” While the practice of “honor suicide” upon the master’s death has lingered throughout Chinese history, the second type of human sacrifice, renji 人祭 (lit. “human sacrifice”) is practiced only during the Shang dynasty period, and also the most massive in scale in terms of number of people killed in a typical renji ceremony. The demographic pattern of Shang sacrificial victims is also quite interesting. Sacrificial burial victims (or supposedly “pious volunteers”) were mostly personal slaves (i.e. house servants), and therefore, in sacrificial burial archaeological sites in China, an even mix of male and female human remains could be found. Renji victims, on the other hand, appear to be predominantly male. Unlike sacrificial burial or xunzang, the people sacrificed for renji were not personal slaves, but mostly prisoners of war and field slaves (keep in mind that Shang field slaves were typically captured from distant lands outside the Shang domain).

Specifically, studies found that Shang dynasty human sacrifice functioned as prayers to Shang-Di to deliver the Shang people from major calamity. This type of sacrifice involving the killing of humans would only take place during periods of severe food shortage, usually due to drought or war.

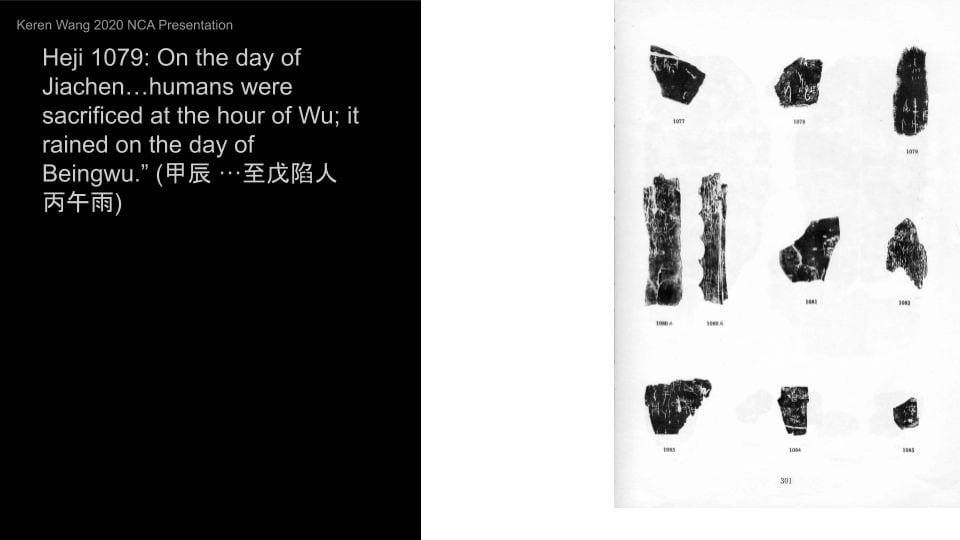

Hundreds or even thousands of captive slaves might be executed during a ritual sacrifice ceremony by means of mass burial after decapitation and/or bloodletting (see Heji fragment 32035 below). The corpses of the victims, along with their severed heads, were buried in mass sacrificial pits or collectively incinerated, to placate what they thought was an angry Shang-Di. Oracle bone inscriptions refer to such sacrificial human blood as qiu (氿, “torrent”), but the precise method for extracting the sacrificial blood remains unknown.

The largest human sacrifice event was attributed to Shang king Wu Ding (1250–1192 BC), as seen in Heiji fragment 1027-1 below, where more than one thousand slaves and war captives and offerings were allegedly slaughtered during a single divination ceremony.

The dichotomization of celebratory and solemn sacrificial rituals also applies to religious practices by the ruling class in the mid to late Shang period. There were instances of total oblation rituals which involved the taking of human life as offerings to Shang Di. There were also instances of substitutive sacrifices which involved burning and destruction of ceremonial vessels and food items as offerings. It is important to note that oblative and substitutive forms of sacrifice differ only not only in terms of their lethality but also in terms of the occasion they were performed. Whereas substitutive rituals were performed typically during calendrical festival occasions to honor the spirit of dead ancestors, oblative human sacrifices were practiced as non-calendrical responses to war and natural calamity. The latter form of sacrifice invariably involved the ritual suspension of nomos (pre-existing formal and customary social protections) pertaining to the taboo of taking human lives. The ritual divination practice in this sense functions as a legitimation rhetorical device, reframing cruel acts of mass violence by the Shang rulers as “necessary” and “justified” performance of a supra-human mandate.

These two modes of Shang period sacrifice rituals represent the adaptive strategic framing of sacrifice as the “appropriate” symbolic response for different communal exigencies. The underlying exigence for substitutive sacrifice serves similar ends as all calendrical feasts of religious and traditional nature; that is, to seek to inculcate commonly held values and norms of behavior via predetermined activities revolving around collective food preparation and consumption, thereby automatically implying, via repetition, a collective sense well-being and continuity with the past.